This is part two on the lesson in adult catechesis on how we got the Bible. Click here if you want to go to the Old-Testament Lesson.

This is part two on the lesson in adult catechesis on how we got the Bible. Click here if you want to go to the Old-Testament Lesson.

The Early Church

We looked at how we got the Old Testament. The Church met in council to state which books were Scripture because three traditions had developed, one of which held that the books of what we call the “Apocrypha” did not belong in the Bible. In 397 AD, at Carthage (geographically in Tunisia today), the Church rejected that view and affirmed that all the books of the Septuagint, the Greek-language Bible of Jesus, His Apostles, and the early Church, was the Old Testament. Those books would be today’s Roman-Catholic Old Testament or the Protestant Old Testament with the Apocrypha.

But the Church also had to deal with issues related to what books belonged in the New Testament. And so, at that same council at Carthage in 397 AD, the Church also listed what books were the New Testament. (There is the question of why the Church waited so late. Part of it was because for much of the time before then, Christianity was illegal and so could not meet in such councils. Second, clarity was needed about understanding Jesus in His divinity and humanity, which was more important of an issue.)

Early in the Church, the books that we all recognize as the “New Testament” were not universally agreed on in all places. Like the Old Testament, there were books that some thought should not be in the New Testament. This was for various reasons. Some doubted that a particular book was of apostolic origin. Now, why was that important? It was because Jesus specifically promised to the Apostles, “The Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything and remind you of everything that I have told you” (John 14:26).

And so the Church discussed, “Should James be in the New Testament? He was Jesus’ stepbrother, not an Apostle?” Or, “Who’s the author of Hebrews? It theologically sounds likes Paul, but it’s not his Greek. Paul wasn’t that good in writing Greek.”

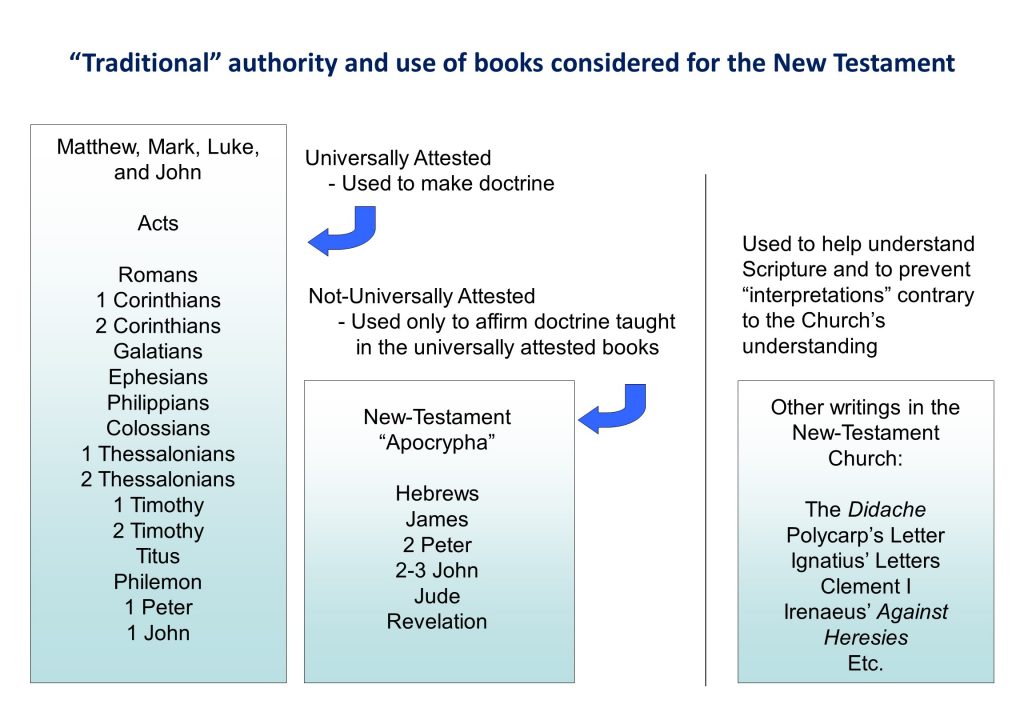

These disputed books, which some contended shouldn’t be in Scripture or should be treated as second-tier books were: Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 2-3 John, Jude, and Revelation. Like the Old-Testament Apocrypha, some in the early Church considered these books to be Scripture, but not canon. (Here’s what the difference is: A canonical book of Scripture is a book from which we may use to make or create doctrine. A non-canonical book is one from which we may only use to affirm the doctrines that the canonical books have in them.)

Others doubted a book because of its content. Some said, “We know the Apostle John wrote Revelation. But it has a lot of wacky stuff in it!” Revelation then had much discussion, even though we find it on almost every list of what books should be in the New Testament before the Council of Carthage met in 397 AD.

What makes all this even more complicated was the discussion that dusted the air about what to do with the books that everyone knew an Apostle didn’t write, even indirectly. For instance, the Church used a document called the Didache, which was used to teach adult Gentile converts coming into (then) an ethnically Jewish church. What should we do with that? What about the Shepherd of Hermas, which was an apocalyptic book like Revelation?

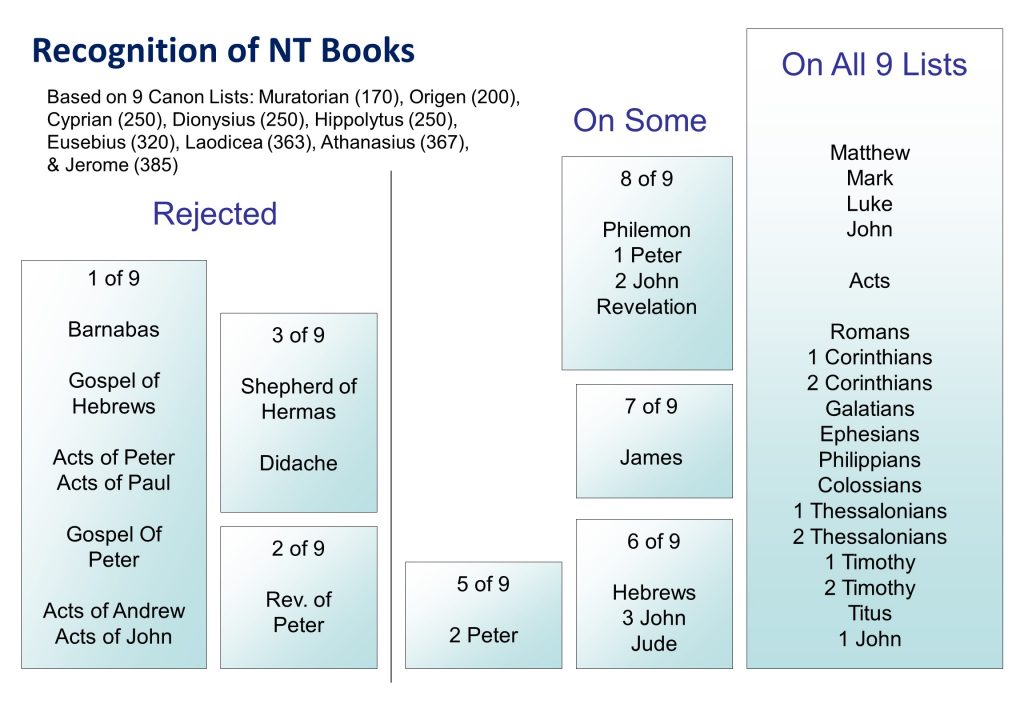

Looking at the various New-Testament book lists that existed before the Council of Carthage, this is what we find. Nine lists floated around cataloging the different books of the New Testament. The boxes below show how many of those lists considered a book as New-Testament Scripture. The “Rejected” columns are those books that didn’t “make the final cut” to become part of the New Testament. The “On Some” or “On 9 Lists” show the books that did “make the cut.”

The Old Testament was easy. We inherited the books of the Septuagint as our Old Testament, and the Council of Carthage simply affirmed that. (Note: Rabbinical Judaism in the mid-2nd century rejected the Septuagint, including the books of the Apocrypha. This was, in part, because they believed that Christians were too successful in converting Jews to become Christians using the Septuagint.)

Unlike the Old Testament, the Church had no such inherited collection of books for the New Testament. Thus, at Carthage, the Church used several criteria to determine if a book should be in the New Testament.

An Apostle as the Author

Did a book have an Apostle as the author? This even included an Apostle being behind the text, even if he may not have written it directly. Many of Paul’s epistles, in part, were this way. He usually used a pastor as a scribe who also helped write the epistle.

For example, in the book of Galatians, Paul only physically wrote the conclusion. He used a scribe to write down everything else. Paul wrote at the end of the book: “Look at what large letters I use as I write to you with my own hand!” (Galatians 6:11).

Luke was a Gentile convert, a physician. Yet, his Gospel and the book of Acts are his compilation of research, writing down what he learned from the Apostles. Mark was not an Apostle, but his Gospel is considered the “Gospel according to St. Peter.” Luke may have been the scribe for the book of Hebrews and wrote the conclusion for Mark’s Gospel (Mark 16:19-20).

Catholicity

Catholic, Greek, kataholou, meaning, that which is according to the whole. Did a particular book teach the catholic faith, that is, the faith the Church universally believed, taught, and confessed from the beginning?

- Discuss: How could the Church make such a requirement? Think about how the Church functioned before her congregations had any New-Testament texts.

But it was more than that. Was a particular book read and preached on widely throughout the Church, not just in one geographical area?

Using those criteria, the Council of Carthage declared what the books of the New Testament were. Fortunately, we haven’t had any movements within the Church that successfully removed some books of the New Testament like we have had with the Old.

Understanding the Distinction between Scripture and Canon

Historically, the Church chose to treat the group of books that all could not affirm as Scripture as not being canonical, those books from which the Church uses to make doctrine. This was a choice to recognize the “weaker brother” (Romans 14:21), those who had some doubts about the “disputed” books in the New Testament. We see Jesus do this when He used the Torah (the five books of Moses) to teach the resurrection to the Sadducees because they didn’t recognize a larger Old Testament (Matthew 22:32).

Note: It is not for the “weaker brother” to dictate what is, such as which books are Scripture, but for the “stronger brother” to decide how best to act.

Today, that distinction of some books having less credibility because they were disputed in the early Church is gone. So, the sensitive treatment of those books is no longer needed. But this was how the Church, at times, once operated.

The Didache helps us understand baptism

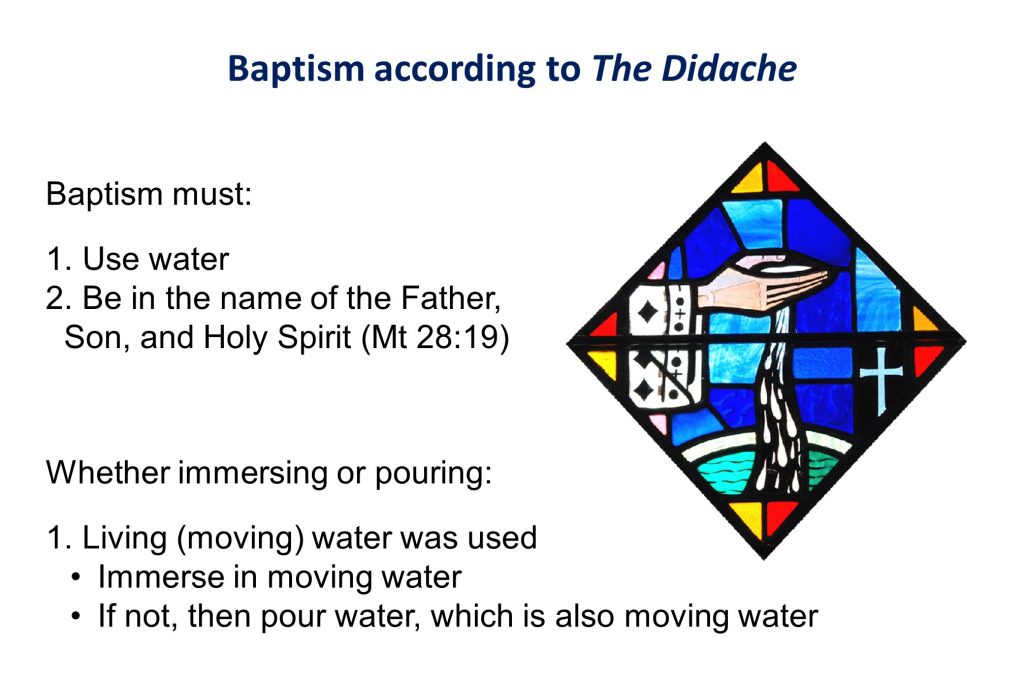

The Didache is not Scripture. But it is a first-century document the Church used to teach Gentile converts what living the Christian life looked like. That document reveals the early Church’s understanding of baptism.

Didache 7:1-3: As for baptism, baptize in this way: After explaining all these things, baptize in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit in living [moving, or what we call “running”] water. But if you do not have living water, baptize in other water. And if you do not have cold water, then use warm water. But if you have neither, pour water on the head three times in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.

- According to The Didache, was water immersion required for a baptism to be a baptism?

- What does this say the meaning of the word “baptize” to first-century Greek speakers?

- What do we find in common between immersing in “living water” and pouring water on the head?

John 4:10, 14:

[Jesus told the woman at the well:] “If you knew the gift of God and who it is asking you for a drink, you would ask Him, and He would give you living water…. The water I will give him will become a become a well of water for him, springing up to eternal life.”

For the early Church, using “living water” was more important than immersion because it testified to the eternal life Jesus gives through baptism.

Clement’s letter to Corinth (96 AD) helps us understand “justify” (dikiaoo)

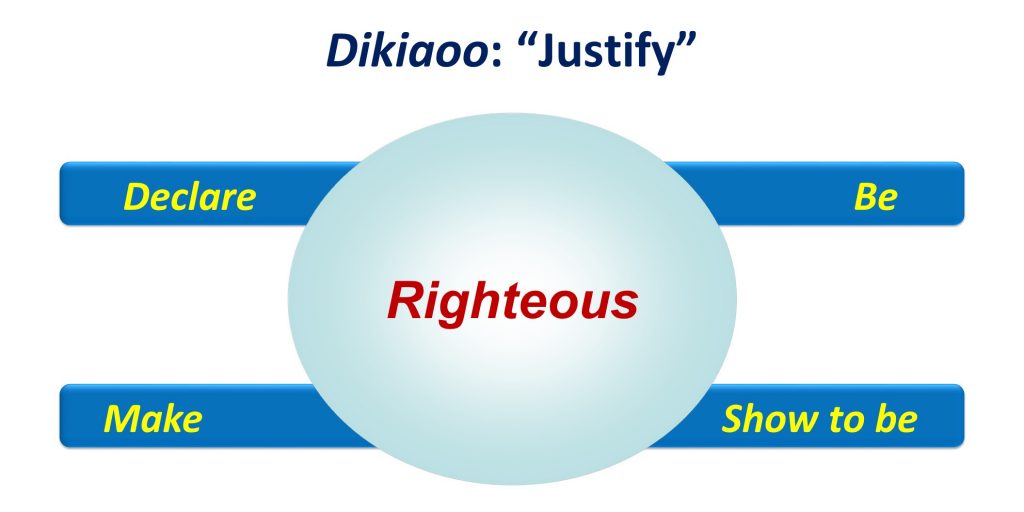

When we read James and Romans in the New Testament, we may think they contradict. For if we don’t understand the range of meanings for the word “justify,” we will come to that conclusion (or come up with some delusional workaround). To help us understand “justify” as the 1st century, Greek-language speaker would, we turn to Clement, the 4th Bishop of Rome. He wrote a letter to Corinth because they were having some problems (no surprise here!).

In 1 Clement 30:3, we read: “Let us be justified by works and not by words.” Clement wrote that sentence to encourage the Corinthian Christian to be humble and not boastful, letting his praise come from God and others, not himself. When Clement said not to boast, the question wasn’t how someone became righteous, but how he lived out or showed that righteousness. Here, Clement used “justify” to mean “show to be righteous”: Show your righteousness by your deeds, not your words.

Clement also wrote: “We, having been called through God’s will in Christ Jesus, are not justified through ourselves or through our own wisdom, understanding, piety, or works that we do in holiness of heart, but through faith” (1 Clement 32:4). Here, Clement used “justify” to show how someone is righteous before God: We are not righteous by what we do but through faith.

Clement doesn’t contradict himself. What he does do is show us the range of meanings for “justify” in the Greek language, which we do not have in English. Clement uses “justify” to mean “show to be righteous” and also “made righteous” or “declared righteous.”

Greek language, which we do not have in English. Clement uses “justify” to mean “show to be righteous” and also “made righteous” or “declared righteous.”

Those same two meanings of “justify” also show up in the New Testament. In Romans, Paul used “justify” to mean to be “made and/or declared righteous.”

- Romans 3:28: “We maintain that a person is justified [made righteous before God] by faith apart from the works of the Law.”

James used “justify” to mean “show to be righteous.”

- James 2:24: “You see that a person is justified [shows that he is righteous] by works and not by faith alone.”

Next week: We look at what Scripture says about the role of Scripture and how to read it.