To help resolve a theological division in the Church, Emperor Constantine hosted the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. The Council defined Jesus as homoousios, of the same Divine substance as God the Father. This was not the desired term because it could be misunderstood as Jesus only being an extension of the Father, not a separate Person. Still, it was adopted because the Arians could not accept such a term.

The Last “Pagan” Emperor

The last “pagan” emperor, Julian, ruled from 361-363 AD. He insisted only those who believed in the traditional Roman gods could value the literature on which the foundation of Roman society was based. So, he passed an edict banning Christians from teaching.

All who teach should be men of upright character, who do not harbor any irreconcilable opinions from what they publicly teach…. I applaud teachers even more if they do not speak falsehoods and condemn themselves by thinking one thing while teaching their students another. Was it not the gods who revealed their learning to Homer, Hesiod, Demosthenes, Herodotus, Thucydides, Isocrates, and Lysias? [Letter 36: Rescript on Christian Teachers]

The reaction to Julian’s edict was almost universally hostile and was revoked after he died in 363. Still, Christians had found a way to reconcile teaching the classics of Roman culture while being a Christian. Basil of Caesarea (330 – 379 AD) wrote:

Pagan learning is not unprofitable for the soul … [However,] you should not study everything they write without exception. When they recount the words and deeds of good men, you should both love and imitate them, earnestly emulating such conduct. But when they portray wicked men, you must flee from them and stop up your ears, as Odysseus is said to have avoided the song of the Sirens. [Address to Young Men, 4]

- How did Christianity “adapt” to exist within a variety cultural settings?

- Discuss the precedent of the Apostle Paul similarly adapting at Mars Hill (Acts 17:22-31).

The emperor who succeeded Julian was Theodosius, who grew up in Spain as a Christian. When he became Emperor, he refused the traditional title of Pontifex Maximus, “High Priest.”

The Spread of Christianity into Europe

The Germanic Peoples

In the 4th century, Christianity made inroads south into Ethiopia, east into Persia, northeast into Armenia and Georgia, and north into Europe. We will only look into Europe because of time constraints and because our Christian roots link us back to Europe.

In 264 AD, Gothic tribes from north of the Black Sea invaded Asia Minor and enslaved people living in the Roman Empire, including many Cappadocian (today in western Turkey) Christians. Among them, was a couple whose daughter, married to a Goth, who gave birth to a boy named, Ulfilas (311 – 383 AD. He later became the “apostle” to the Goths and their first bishop.

Sent with others by the Gothic leader as an ambassador in the time of Constantine (for the barbarians in those parts owed allegiance to the Emperor), Eusebius [the Bishop of Constantinople] and the Bishops of his party chose Ulfilas to become the Bishop of the Gothic Christians. Among the matters to which he attended, he developed an alphabet and translated the Scriptures into their language. [Philostorgius, Church History, 2.5]

In the 370s, the Gothic tribes became part of the Roman Empire, adopting Ulfilas’ teachings as the foundation of their understanding of Christianity. Though now Christian, the Goths remained a warring people and continued to attack Roman cities. What changed was when they sacked a city, they usually spared the churches and those who sheltered inside, as they did at Rome in 410 AD.

With the Goths, Christianity took on a different hue since their culture did not have a sense of personal guilt. For them, needing a Savior from sin did not concern them. So, understanding Gothic culture, Ulfilas translated “Savior” as “Healer.” Though requiring a Savior mattered little to them, everyone needed a Healer. Christianity gave them an ability to see beyond the suffering of life as capricious events, unlike regret over personal sins, which did not connect with them in any significant way.

The Franks

Even before 200 AD, we know from Irenaeus (135-202 AD, Lesson 10) about Christianity already existing in Gaul (France). Outside the metropolitan areas, however, Christianity had spread little. Even by the late 300s, few inroads were made into the countryside.

Two centuries later, all of Gaul was different, operating within a Christian social fabric. Paganism as an overt, public force no longer existed in Gaul or Spain, except among the Basques. So, what happened? Christian writer, Sulpicius Severus (363 – 425 AD), tells us of Martin of Tours (316 – 397 AD).

One day during a bitter, cold winter, Martin was dressed only in his military cloak and weapons. At the gate of the city of Amiens, he came across a naked beggar. The man pleaded for others to show pity on him, but they all walked past. Filled with God’s grace, Martin understood this man was meant for him since the others showed him no mercy.

But what was he to do? Apart from his cloak, he had nothing, for he already helped others with what he had. So, he unsheathed the sword at his side and cut his cloak in two, giving half to the beggar and then put the remaining piece on again. [Life of Martin, 3.1–2]

After this, Martin lived as a Christian. No doubt, he was familiar with Christianity’s teachings to declare himself and publicly live as a Christian. It was at this time, in 355 AD, that Julian became “Caesar” in the West, with his troops later proclaiming him “Augustus” in 360. Julian attempted to purge the Army’s officer corps of Christians. So, in 356 AD, a 40-year-old Martin was retired, having fulfilled his required term of 25 years.

Martin then chose to become a monk, during which time He pondered the function of the monastery. Unlike the monasticism in Africa, his wanted a “muscular” Christianity where monasteries did not become an “escape” for contemplation but served as mission outposts.

As a monk for several years, he was elected as the Bishop of Tours. As Bishop, he used his monks as part of “force” to deconstruct paganism. This helped expand the Christian faith into the northern and central areas of, what is today, modern France. He was popular among the poor, wearing peasant clothing and having a rough-and-ready manner (perhaps a carryover from his time of military service). Though unpopular with the “elite,” the peasants loved him. (A current example may be President Trump’s mannerisms and speech, which our nation’s “elite” disparage and consider as unpresidential.)

The Britons

We aren’t sure about exactly how and when Christianity first spread into Britain. Most historians believe Christianity entered Britain during the second half of the 2nd century through commercial and military contacts between Britain and Gaul.

Tertullian (160-225 AD, Lesson 12), mentioned the Britons on a list of peoples who had become Christian (Against the Jews, 7). Origen (186-255 AD, Lesson 12) tells of Christianity existing in Britain, though acknowledging most Britons had not yet heard the Gospel (Homilies on Luke, 6). Later, in the 4th century, Eusebius of Caesarea (263 – 339 AD) wrote of Christianity crossing over to the British Isles (Proof of the Gospel, 3.3).

The Future: The Changing Role of the Bishop in the West

As Rome began to crumble within by the weight of its Empire, the last tatters of imperial control deteriorated in Britain, Gaul, and Spain. In the 5th and 6th centuries, as the distinctive marks of a functioning society disappeared, bishops became the natural leaders of their local communities as the last remaining last vestiges of imperial authority.

We find an example of this in Germanus (378 – 448 AD) of Auxerre, today in Burgundy, in north-central France. He was born in 378 AD. In 418, his bishop died—but that region of Gaul was now without its Empire. The Christian community of Auxerre insisted Germanus become their next bishop.

As Bishop, he put together a taxation system to provide governmental services. He organized a functioning army to protect the people from Goar, the King of a Germanic group called the Alans. The services of relief for the destitute, public works, education, healthcare prison visiting, ransoming of captives, became the responsibility of bishops.

- Why did bishops need to manage these services?

- Discuss how the changing role of bishops, which included secular power and wealth impacted both Church and State.

The Council of Carthage: 397 AD

In 325 AD, the first ecumenical council took place at Nicaea to denote how Jesus and God the Father were the same in Being, yet different in Person. This was primarily an Eastern, Greek-language problem.

After clarifying the divinity and humanity of Jesus, the Church now dealt with another problem. Three traditions had developed concerning the Old Testament, which were not fully compatible. This primarily was a Western, Latin-language problem.

Athanasius of Alexandria (297-373 AD): The Anagignoskomena

We learned of Athanasius in Lessons 15 and 16. He was the first Church Father to use the word “canon” (meaning “rule” or “norm”) to characterize the contents of Scripture. This was a new designation, for the Jews of the Old Covenant spoke of Scripture as holy, with a book being either sacred or profane.

In his bishopric, Athanasius had to deal with some presbyters preaching and teaching from spurious texts. So in the 39th Festal Letter, dated January 7, 367, Athanasius wished to specify Scriptural texts no one doubted from those which some had doubts about.

Of the Old Testament, there are 22 books. For, as I have heard, it is handed down that this is the number of the letters among the Hebrews; their respective order and names being as follows. In this order thus far [he then lists all the books in today’s Protestant Old Testament, adding Baruch (the epistle of Jeremiah) and omitting the book of Esther] constitutes the Old Testament.

Next, Athanasius listed the books of the New Testament. However, he also added other books that were not among the books “that are canonized,” which the Fathers also handed down to be read, called “anagignoskomena”:

But for more exactness, I further add because I must. There are other books [of Scripture] besides these not included in the canon. The Fathers appointed these books to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness. The Wisdom of Solomon, the Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, Tobit, and that which is called the Teaching of the Apostles [The Didache, Lessons 4 and5], and the Shepherd [of Hermas].

So, Athanasius separated the Bible into two categories: The canonical books of Scripture and the Anagignoskomena. The Anagignoskomena were to be used for preaching and teaching but not to establish doctrine since they were not canonical, the norming books. This becomes the tradition in the Eastern Orthodox churches.

Cyril of Jerusalem (313 – 386 AD): The Deuterocanon

Cyril was ordained and later became the Bishop of Jerusalem. Like Athanasius, he also had problems of non-scriptural books being used in his congregations. So he also composed a list of the scriptural books.

Learn also diligently, and from the Church, what are the books of the Old Testament, and what are those of the New…. of the Old Testament, as we have said, study the 22 books. If you desire, strive to remember them by name.

For of the Law the books of Moses are the first five: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Next is Joshua … and the book of Judges, including Ruth, counted as seventh. And of the other historical books, the first and second books of the Kings are among the Hebrews one book; also the third and fourth one book. And in like manner, the first and second of Chronicles are with them one book; and the first and second of Esdras are counted one, and Esther is the 12th. These are the historical writings.

Those written in verses are five: Job, the book of Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon, which is the 17th.

After these come the five prophetic books: The 12 prophets are one book, Isaiah, of Jeremiah one, which includes Baruch, Lamentations, and the Epistle. Also, there is Ezekiel and Daniel, the 22nd of the Old Testament.

Then the New Testament [he then lists all the books of the New Testament]. Let all the rest be put aside in a secondary rank [deuterocanon].

Cyril differs from Athanasius by including Esther among the “canonical” books while Athanasius placed it among the Anagignoskomena.

For Cyril, this second category of books was deuterocanon, canonical books of secondary rank. So, Cyril held them in higher regard than Athanasius, but still did not consider them to be first-level canon. This becomes the tradition in the West, of Roman Catholicism, until the 1400s.

Notice we do not find complete concurrence on the books between Athanasius and Cyril, even among the secondary texts.

Jerome (347 – 420 AD)

Born in Stridon in Dalmatia (today, around Serbia), Jerome was baptized when 20 years old. Interested in theological and biblical studies, he entered school and later became a presbyter and monk. Eventually, he settled in Rome in the 380s. A bit incorrigible and with an appetite for controversy, he was forced to leave. He went East and lived as a monk in Bethlehem, where he spent the rest of his life.

Though a curmudgeon, others still recognized him for his language skills in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic. Pope Damascus (Pope, 366-384 AD) commissioned him to translate a new Bible version into Latin. The Latin Bible in use, called “the Old Latin version,” was a hodgepodge of various translators and had as many variations in the text as there were manuscripts.

So, Jerome began translating from the Greek Septuagint as Christian translators had done since the beginning. He was merely following the example from the Apostles since more than 80% of the Old Testament references in the Greek New Testament are from the Septuagint.

Jerome, however, became frustrated because he had numerous versions of the Septuagint to sort through to arrive at an original. By contrast, he had a Hebrew text available to him in a standardized and stable version. Since the Septuagint was a translation of the Hebrew, why not translate directly from the Hebrew? He called this “Hebrew Verity.”

What Jerome didn’t realize, which we do today, is the “original” he used contained revisions and copying errors. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls revealed that parts of the Septuagint preserved remnants of a more ancient Hebrew textual tradition now lost in what we call “the Masoretic Text.”

Jerome concluded if any books were not in the “original” Hebrew, they could not be inspired Scripture and, therefore, must be rejected. (Ironically, he didn’t do this with the original Aramaic parts of Daniel). He called these rejected books “apocrypha,” meaning “hidden.”

The Solution

Jerome retained the Apocrypha books in the Old Testament. However, he caused a crisis in the Latin West because he stated his opinions in his prefaces of the Latin Vulgate. So, in the place where the Western Church first used Latin, bishops met to resolve this issue.

In 397 AD, at Carthage (today in Tunisia), the Western Church made this decree:

… nothing except the canonical scriptures should be read in the Church under the name of the divine scriptures. The canonical scriptures are [listing all the books of the Septuagint, including the Anagignoskomena/Deuterocanon/Apocrypha]. Moreover, of the New Testament … [lists today’s New Testament, not including The Didache and The Shepherd of Hermas, we declare] the Church beyond the sea may be consulted regarding the confirmation of this canon. Also, allow the sufferings of the martyrs to be read when their anniversary days are celebrated.

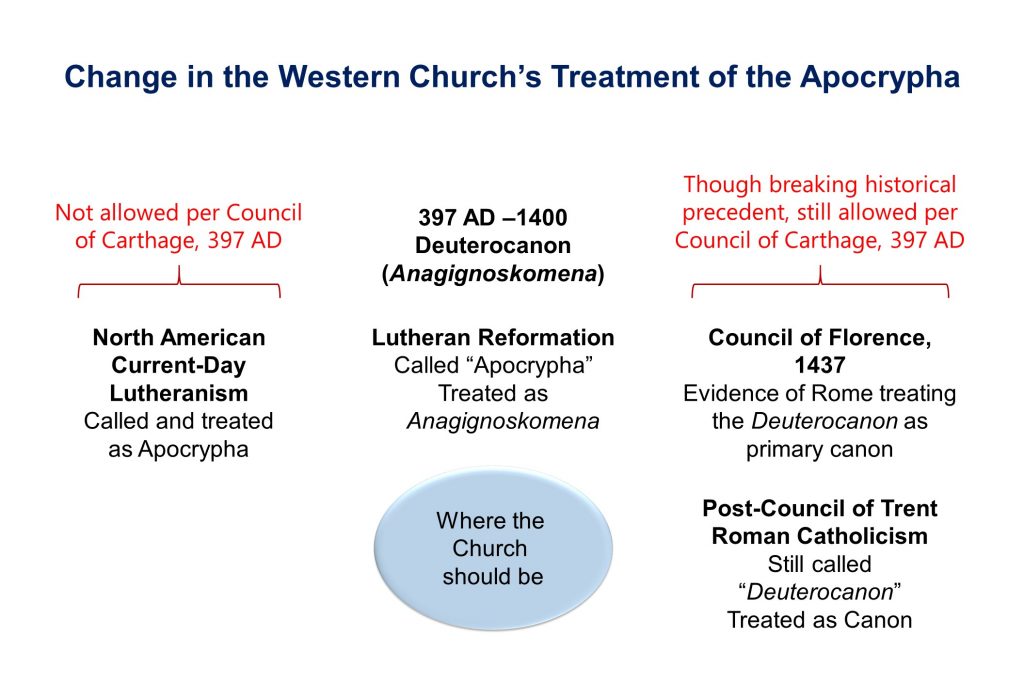

Though declaring all the Scripture to be “canon,” the Church still operated with a two-tiered Old Testament: The Anagignoskomena in the East, the Deuterocanon in the West. The Church found both views as acceptable—but rejected the Jeromian apocrypha view.

The Lutheran Church

Martin Luther’s (1483 – 1546 AD) most-famous quote about the Apocrypha comes from his preface to the Apocrypha in his German translation of the Bible. These books “are not held to equal the sacred Scriptures” but are “nevertheless useful and good to read” (LW, vol. 35, pg.337).

Luther did not remove the Deuterocanon from the Bible. What he did, instead, was to move it into an unnumbered appendix, which he called “Apocrypha” at the end of the Old Testament. Luther also did this for the New Testament, moving the books he didn’t like into an unnumbered appendix: James, Hebrews, Jude, and Revelation. After Luther’s death, the Deuterocanon’s placement as “Apocrypha” remained while the books of the New Testament were restored to their previous locations.

Despite Luther’s personal opinion, he removed no books from the Bible. What happened was the Lutheran church adopted the Anagignoskomena view of Scripture but adopted Jerome’s terminology. We see this The Apology to the Augsburg Confession, chapter 21, para 9:

We grant that angels pray for us. For there is a passage in Zechariah 1:12, where an angel prays, ‘O Lord of hosts, how long will you withhold mercy from Jerusalem?’ To be sure, concerning the saints we grant that in heaven they pray for the Church in general, just as they prayed for the Church in general while alive. However, no passage about the dead praying exists in the Scriptures, except that of a dream recorded in 2 Maccabees 15:14.