For Lutherans, our Formula of Concord reads:

We believe, teach, and confess that the only rule and norm according to which all teachings, together with all teachers, should be evaluated and judged are the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures of the Old and of the New Testament alone. [Ep, Summary, 1]

Thus, we find that Scripture is not the only source for what we believe, teach, and practice, but it is THE judge and evaluator.

Protestants understand “Sola Scriptura” differently. For them, “Scripture Alone” means this.

For Roman Catholics, “Sola Scriptura” is a foreign concept, which they do not hold, and to which they do not agree. For them, this is how Scripture fits into their worldview.

According to Scripture, both Scripture and the Church have a role in our lives.

The prophetic and apostolic Scriptures of the Old and of the New Testament

Our Lutheran Confession also describe which “Scriptures” are “the only rule and norm according to which all teachings, together with all teachers, should be evaluated and judged.” Notice that our Confessions do not say “all Scripture” or simply “Scripture.”

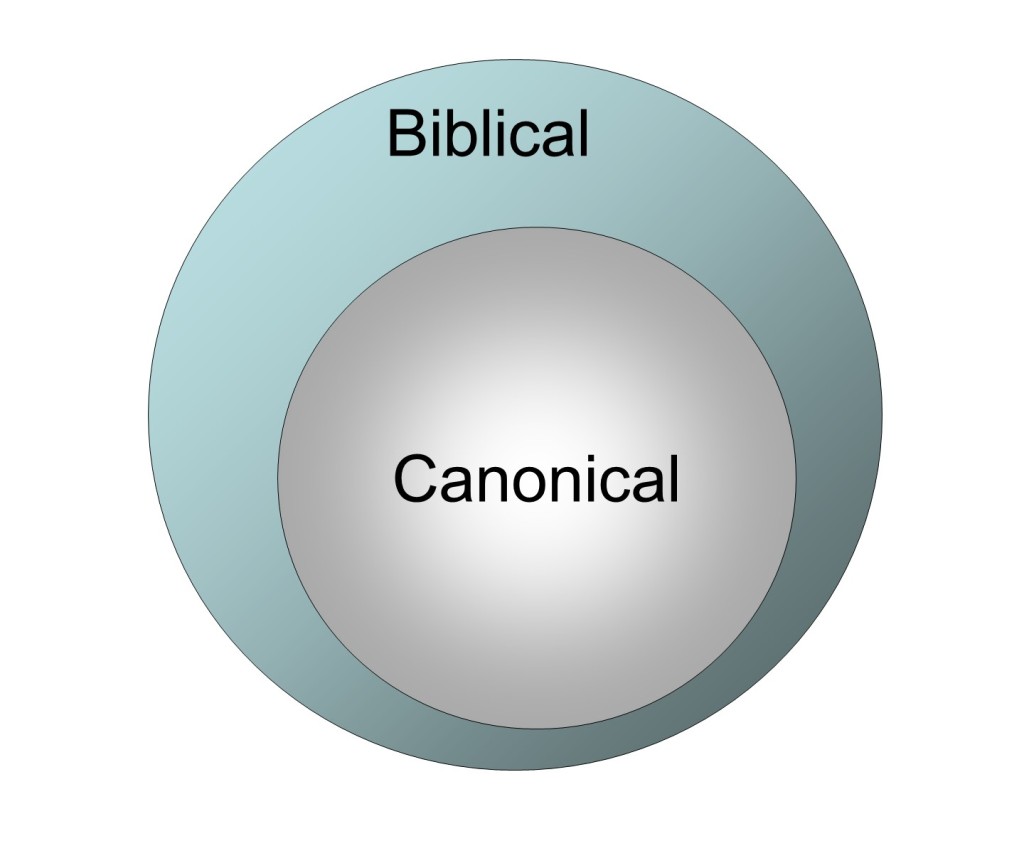

That means that “prophetic and apostolic” is a subset of all Scripture. Not all of the Old Testament is “prophetic”; not all of the New Testament is “apostolic.” The “prophetic and apostolic Scriptures” is simply another way to say the “canonical Scriptures.” Like, “prophetic and apostolic,” “canonical” is also a subset of the Scriptures.

The one time our Lutheran Confessions use the term “canonical Scriptures” is when they quote St. Augustine: we must not “hold anything contrary to the canonical Scriptures of God” (AC, XXVII, 28). Since our Confessions do not list the books of the Bible (you would think they would, but they don’t), nor which of those are “canonical,” we have to do some sleuthing.

And we should! For how do we know that the Bibles we use didn’t add or take away books. And how do we know which books are canonical?

The Old Testament Scriptures

The Jews of Jesus’ day were not a single, monolithic, religious entity. They were split into groups, somewhat like the Church is today. They had separated into competing groups with their separate schools, each claiming to be the true expression of Judaism.

Some of these groups held different opinions about which books were Scripture. By “Scripture,” think of the Greek-language Septuagint, which had become the de-facto Old Testament for most of the Jews.

- The Sadducees only accepted the first five books of the Bible and rejected the rest.

- The Essenes didn’t accept Esther, but did accept Tobit, Sirach, and Enoch (not in the Septuagint).

- The Pharisees were dominated by two schools: Shammai and Hillel.

- The school of Shammai believed that Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, and Esther weren’t Scripture.

- The school of Hillel believed they were.

- Only the school of Hillel held that all the Septuagint was Scripture, without adding anything to it or taking away.

So, to understand what books make up the Old Testament, we cannot look to the Jews, for they couldn’t agree! For Christians, only one first-century Jewish group was the true expression of Judaism—the Christians. Jesus Christ and His Apostles set the norm for Christian belief and practice (1 Corinthians 11:1-2, Philippians 3:17).

So, what matters is what books they accepted as Scripture!

Tobit 3:7-8, 15

Raguel’s daughter, Sarah, was insulted by her father’s maids. For she was married to seven husbands, but the evil demon Asmodeus had slain each of them before he could be with her as his wife…. [Sarah said,] “Seven husbands of mine have already died. Why should I live?”

Read Matthew 22:23-29

- Which books did the Sadducees only hold to be Scripture?

- How did they try to undercut Jesus’ understanding of the resurrection and what books comprised the Scriptures?

- What book did Jesus refer to as Scripture, which the Sadducees didn’t consider to be Scripture?

- What does that say about most of the Old Testaments in our Bibles?

The Scripture according to the Church

Today, we know what books belong in the Bible because the Church (“the pillar and foundation of the truth,” remember?) spoke definitively on the matter at the 3rd Council of Carthage, in 397 AD. In Canon 24, the council wrote:

Besides the canonical Scriptures, nothing shall be read in church under the name of divine Scriptures. Moreover, the canonical Scriptures are these: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings], Paralipomena [Chronicles] two books, Job, the David’s Psalter, the five books of Solomon [Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Wisdom, and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus)], the twelve Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, Tobias, Judith, Esther, Ezra two books, Maccabees two books.

This list is the Protestant Old Testament—but also the books of the Apocrypha.

The Three Old-Testament Traditions

To make sense of the Council of Carthage, we need to understand why that Church council met. It met to resolve which books were Scripture because three traditions had developed within the Church.

Athanasius (295-373), the Bishop of Alexandria, held that what we call “apocrypha” was anagignoskomena. He considered those books worthy of being read, studied, and preached on in the Church. However, he held that doctrine was not to be created from such books.

Cyril (315-386), the Bishop of Jerusalem, held that what we call “apocrypha” was deuterocanon, a second-tier level of canon. He considered them canonical books, but of secondary rank. This classification changes, in practice but not wording, later within the Roman Catholic Church.

Jerome (347-420), Translator: He was commissioned to make a new translation of the Bible into Latin, which became the Vulgate. Jerome was the first Church father who wanted to categorize the apocrypha as NOT part of the Old Testament.

When the Church declared what books were Scripture, she affirmed that Athanasius’ and Cyril’s views were acceptable, but Jerome’s was not.

Here’s irony: The Lutheran Church adopted Jerome’s terminology (apocrypha) while moving away from deuterocanonical view (second-tier canon) to the Eastern-Orthodox view (anagignoskomena).

The prophetic, canonical Scripture of the Old Testament

This is the Old Testament, but not the Old-Testament Apocrypha. We do not use the Apocrypha to judge and evaluate teaching and practice within the Church.

Biblical versus Canonical

The apostolic, canonical Scripture of the New Testament

These are the books of the New Testament that no one in the Church doubted was of apostolic origin (whether directly or indirectly. For example, Mark was by the Apostle through Mark; Luke and Acts were by a bit by Peter and mostly Paul through Luke.)

Martin Chemnitz (1522-1586) was the first person to list the books of the Bible in the Lutheran Church. In Ministry, Word, and Sacraments, Chemnitz labeled the Apocrypha as the “apocryphal books of the Old Testament.” He treated the Old-Testament Apocrypha the same as he treated the “Apocryphal books of the New Testament”: 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. These books were biblical, but not canonical.

Thus, we don’t use the New-Testament books of 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation as “the only rule and norm according to which all teachings, together with all teachers, should be evaluated and judged.”