The Apocrypha and Change within the Lutheran and Roman Churches

The Apocrypha and Change within the Lutheran and Roman Churches

Lesson 4

By Pr. Rich Futrell

Jan 23, 2011

Recap

Last week, we learned how the early Church responded to three traditions on the Apocrypha and affirmed the Anagignoskomena and Deuterocanonical views as legitimate. The Church rejected the view that allowed someone to reject the Apocrypha.

The Apocrypha in the Lutheran Confessions

Our Lutheran Confessions do not affirm or deny the Apocrypha, nor do our Confessions even list the books of the Bible! This shows that what constituted the Bible for Lutherans during the Reformation was not in dispute. This means the Lutheran view of what books were in the Bible was simply the same as the Roman Catholic Church.

However, to get the Lutheran view on the Apocrypha, we simply have to see how our Confessions treat them.

Ap, V, 158: “Tobit’s address, regarded as a whole, shows that faith is required before alms, “Be mindful of the Lord, your God, all your days [Tobit 4:5].”

– How do our Confessions treat the book of Tobit when they quote it, as Scripture or as something other than Scripture?

Ap, V, 158: “Afterward, ‘Bless the Lord, your God, always, and desire of Him that your ways be directed by Him [Tobit 4:19].’ This, however, belongs properly to that faith, which believes that God is reconciled to it because of His mercy, and which wishes to be justified, sanctified, and governed by God.”

– Again, how do our Confessions treat the book of Tobit?

Ap XXI, 9: “We grant that angels pray for us. For there is a passage in Zechariah 1:12, where an angel prays, ‘O Lord of hosts, how long will you withhold mercy from Jerusalem?’ To be sure, concerning the saints we grant that in heaven they pray for the Church in general, just as they prayed for the Church in general while alive. However, no passage about the dead praying exists in the Scriptures, except that of a dream recorded in 2 Maccabees 15:14.”

– What do our Confessions call the book of 2 Maccabees?

– Remembering how the Church used the anagignoskomena/deuterocanon, why wouldn’t a dream recorded in 2 Maccabees be used to make a doctrine?

SC, 8th Commandment, Woodcut: A woodcut of the story of Susanna was used in the Small Catechism to help teach the 8th Commandment not to bear false witness.

Martin Chemnitz

Many Lutherans consider Chemnitz to be the 2nd greatest theologian in the Lutheran Church. For Lutherans, Chemnitz was the first to list the books of the Bible, which simply affirmed the view in our Confessions. In Ministry, Word, and Sacraments, he separated Scripture into two categories: those from which the Church makes doctrine and those from which the Church does not.

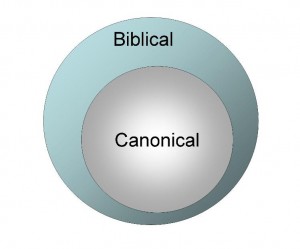

Chemnitz considered the Apocrypha as Old Testament Scripture but labeled them the “apocryphal books of the Old Testament.” He treated the Apocrypha the same as he did the Apocryphal books of the New Testament: 2 Peter, 2nd and 3rd John, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation–biblical but not canonical.

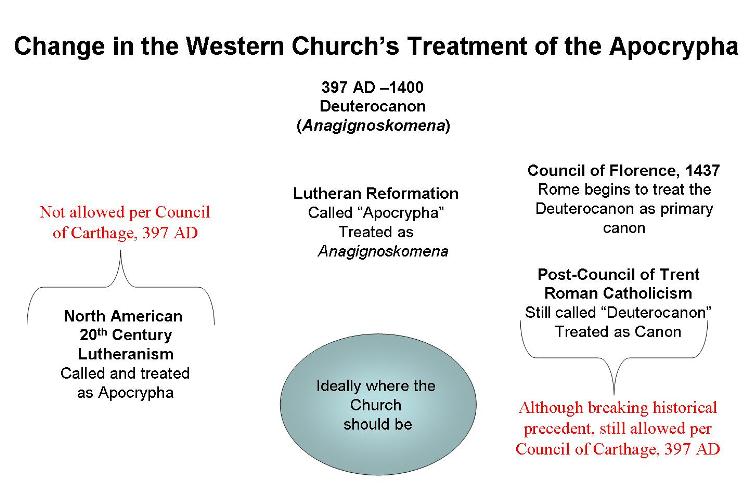

Here we see the Lutheran Church adopt Jerome’s language (apocrypha) but affirm Athanasius’ view (anagignoskomena “that which is worthy of being read”).

– What is the difference between what is canonical and what is biblical?

The Roman Catholic Church Changes

Among the three traditions that had developed in the early Church concerning the Apocrypha, the anagignoskomena tradition became the working practice in the Eastern Orthodox churches. For the Roman Catholic Church, the deuterocanon (second-tier canon) approach became the norm. The New Testament Church at the Council of Carthage (397 AD) rejected Jerome’s view of jettisoning the Apocrypha from the Old Testament (ironically, for us, called the apocryphal view).

However, during the 1400s we see the Roman Catholic Church, in practice, treating the deuterocanon as primary canon at the Council of Florence (1437 AD). During the Council of Trent, we see the shift officially take place within Roman Catholicism. The Council issued a dogmatic decree called “The Sacred Books and the Tradition of the Apostles.” The decree states:

So that no doubt may arise in anyone’s mind as to which are the books that are accepted by this Synod [that is, the Council of Trent], it has decreed a list of sacred books be added to this decree. [The Council then listed the Old Testament including the Apocrypha and the New Testament]

– At this point, did the Council do anything that was not catholic, that is, different from how the Church has always treated Scripture?

Then the Council went on to say: “If anyone, however, should not accept the listed books as sacred and canonical, entire with all their parts … let him be anathema.”

– With that one statement, what official shift had taken place within the Roman Catholic Church on how they treated and used the Apocrypha?

In response to Rome’s breaking with the Church’s historical practice by treating the deuterocanon as primary canon, Chemnitz then hypothesized about treating the Apocrypha in the opposite way. Do we have the authority to reject and condemn the Apocrypha? In his Examination of the Council of Trent, Chemnitz responded, “We by no means seek this” (vol. 1, pg. 189).

So What Happened in the North American Lutheran Church?

In North America among German-speaking Lutherans, every documented German Luther Bible published by Concordia Publishing House contained the Old Testament Apocrypha. The Missouri Synod’s catechetical instruction also presented an awareness of the Apocrypha. The edition of Luther’s catechism initially used in the Missouri Synod was the one edited by Johann Conrad Dietrich (1575-1639). The Dietrich Catechism said:

5. Are there any others besides these canonical books contained in the Holy Bible?

Yes, those which are usually called apocryphal.

6. What are apocryphal books?

Apocryphal books are those respecting whose authors and authority there were doubts in the Church of God; therefore they were publicly used neither to establish, to confirm nor to judge articles of faith.

In the Dietrich Catechism we see that the Apocrypha was still considered biblical but not canonical. However, the tone of the answer gave no one any reason to want to read the Apocrypha.

Ironically, although Dietrich seemed to dismiss the Apocrypha by what he wrote in his explanation to the Small Catechism, he did not act that way as a pastor. Dietrich still saw the Apocrypha as something to be read during the Divine Service–and even to be used as sermon texts. He preached from the Apocrypha book of

Wisdom of Solomon verse by verse in sermons. [This book], according to Dietrich, is to be highly esteemed, most of all because the Holy Spirit has taken it up and perfected it in the manner of heavenly philosophy. (Hebrew Bible / Old Testament: The History of its Interpretation, II: From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment by Magne Saebo, 2008, pg 744)

Following the Dietrich Catechism, the Missouri Synod adopted the Schwann Catechism. In the catechism, the support for the Apocrypha was even less than the Dietrich Catechism. The Schwann Catechism simply reads:

The Old Testament was written in Hebrew and the New Testament in Greek. Our English Bible is a translation from the Hebrew and the Greek. The English Bible which is in ordinary use is called the Authorized Version, or King James Version. It is a translation made by a body of learned men and published in England in 1611, during the reign of James I.

– Based on what the Schwann Catechism reads, what just happened to the Apocrypha within the Missouri Synod (considering by then that the King James Versions no longer had the Apocrypha in them)?

When Franz Pieper wrote His Christian Dogmatics text (still the “official” systematics/dogmatics text for the LC-MS although not used significantly anymore), he wrote, “There is, however, no historical witness for the Apocrypha of the Old Testament. Neither the Jewish Church nor Christ recognized them as canonical [vol 1, pg. 330].”

– From what you’ve learned from earlier lessons, explain how Pieper was wrong.

Paralleling the move in the Missouri Synod from a tepid support of the Apocrypha to neglect and then to rejection was a language change that was happening at the beginning of the 20th century. As English became the predominant language, English speakers brought with them Bibles (not from Concordia Publishing House) that lacked the Old Testament Apocrypha.

For the rest of the twentieth century, the dismissal of the Apocrypha became stronger. By 1943, a new edition of the Schwan Catechism enumerated the books of the Bible: “There are sixty-six books in the Bible: thirty-nine in the Old Testament and twenty-seven in the New Testament,” followed by a list of those books. The entire understanding of distinguishing between canonical from biblical was lost.

Click here to read the final installment on the Apocrypha.