The Monarchy in the Old Covenant

The Monarchy in the Old Covenant

Even before Israel had kings, we find the Law of Moses anticipating that God’s people would become a monarchy like its neighbors:

“When you enter the land that the Lord your God is giving you, take possession of it, and settle in it. Then you will say, ‘I will appoint a king over me like all the nations around me.’ Be sure to appoint over you a king the Lord your God chooses. Appoint a king from your brothers. You are not to set a foreigner over you, or one who is not of your people” [Deuteronomy 17:14-15].

When Israel finally did get their King, he was a disaster. Israel’s first king, Saul, was so wicked that God rejected him and chose another to replace him. He was David, a man who was after God’s own heart (1 Samuel 16:1-13, 2 Samuel 5:4-5, Psalm 89:19-37, Acts 13:22).

King David, after conquering his enemies and building his palace, wanted to build God a Temple(2 Samuel 7:2). David’s plan pleased God; yet God told David that his son (Solomon) would build the Temple, instead. God also promised David that his kingly line would remain forever: “Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me. Your throne will be established forever” [2 Samuel 7:16]. And several other times throughout Scripture, God also repeated and reaffirmed His promise of an everlasting kingdom (Psalm 89:4-5, Psalm 110:1-2, Psalm 132:11, and Jeremiah 33:17).

But what do we find? If you read the Old Testament, you find sin quickly bringing ruin to Israel during its time of kingly rule. The greed of Rehoboam, David’s grandson, caused the kingdom to split into two. The Northern Kingdom formed and installed its own king, Jeroboam (1 Kings 12:4). Foreign powers eventually conquered both kingdoms, at different times, and sent the people of Israel into exile. Only the two tribes, Benjamin and Judah, survived foreign domination and returned to rebuild Israel.

After such devastation, the dynastic succession of David had all but disappeared, since it looked as if no son of David would occupy the throne. Yet, all was not as it seemed. God had promised the true Son of David, the Messiah, would still come one day and rule from his father’s throne forever (Isaiah 9:6-7, 11:1, Jeremiah 23:5, 30:9, Ezekiel 37:24, Hosea 3:5, Micah 5:1-3, and Zechariah 6:12-13).

All of Israel waited in expectant hope for the coming of the promised son of David to restore the kingdom. What was the sign of this restoration? It was the promised woman giving birth to the royal son (Genesis 3:15, Isaiah 7:11, Micah 5:1-3, Jeremiah 31:22, and others).

This sign in itself doesn’t seem that significant. What is so remarkable about a woman giving birth to a baby boy? Each of us is “born of a woman.” Even more, why would a woman giving birth be a sign that God is restoring the house and line of David? We find the Old Testament helping us answer that in the office known as “Queen Mother.”

The Queen Mother

When we think of a kingdom, we often picture a king and a queen as its rulers. But what took place in the house and line of David was different. Kings in the Old Testament practiced polygamy, mainly for political reasons. That is why a king had many queens.

Although a king may have favored one wife over the others, no one wife enjoyed superior rank or authority. We find in Song of Solomon, besides “concubines” and “maidens,” that another word is used to describe some of the women around the king. That work is malikah, the Hebrew word for “queen” (Song of Solomon 6:8). Interestingly, that’s the only time the Old Testament uses the word malikah.

Yet, there was one woman in the royal court who did hold a distinctive office under the king. The title for that woman was “Queen Mother” (Hebrew, gebirah); she was not the King’s wife, but his mother. The Old Testament even mentions the Queen Mother as a member of the royal court (2 Kings 24:12).

To note the difference between being a queen and a queen mother, we contrast these two passages about Bathsheba.

1 Kings 1:16-17, 31, Bathsheba as Queen:

Bathsheba bowed down, prostrating herself before the king. The king asked, “What do you wish?” She said to him, “My lord, you yourself swore to me your servant by the Lord your God: ‘Solomon your son will be king after me, and he will sit on my throne.’” … Bathsheba bowed down with her face to the ground, prostrating herself before the king, and said, “May my lord King David live forever!”

1 Kings 2:19-20, Bathsheba as Queen Mother:

So Bathsheba went to talk to King Solomon for Adonijah. The king stood up to greet her, bowed down to her, sat down on his throne, had a throne placed for the king’s mother, and she sat down at his right hand. Then she said, “I have one small request to make of you; do not refuse me.” And the king said to her, “Make your request, my mother, for I will not refuse you.”

– Discuss the differences?

Solomon Establishes the Office of Queen Mother

Scripture does not directly state when the mother of the King would step into her formal office as Queen Mother. This is something that those in ancient Israel knew from living in the kingdom. However, 2 Chronicles 11:21-22 implies that the Queen Mother stepped into her office when her son was enthroned.

David’s son, King Solomon, set up the office of Queen Mother shortly after he took his father’s throne. Why didn’t Saul or David do that? Their mothers were never the wife of the previous king. That’s why Scripture describes these acts by King Solomon when Bathsheba went to talk to him: “The king stood up to greet her, bowed down to her, sat down on his throne, had a throne placed for the king’s mother, and she sat down at his right hand” [1 Kings 2:19].

We see that the Queen Mother occupied a significant place in the royal court. The Queen Mother’s office was a lifelong appointment. She remained in office even if she had outlived her son. Yet, like the other royal officials of the court, the King could remove the Queen Mother from office if grounds existed to do so. That happened to Queen Mother Maacah. King Asa removed her “from being Queen Mother because she had made an obscene image for the worship of Asherah” (1 Kings 15:13).

Roles of the Queen Mother

1. A Sign of the King’s Legitimacy to be King

What roles did the Queen Mother fulfill? First, it is through her that the King became the lawful, dynastic heir to the throne. For that reason, she became the tangible sign that her son was the rightful king.

For example, before David’s death, two of his sons had laid claim to the throne. They were Solomon, the son of David’s wife Bathsheba (1 Kings 1:11, 2:13) and Adonijah, the son of David’s other wife Haggith (2 Samuel 3:4, 1 Chronicles 3:2). David had sworn an oath to Bathsheba that her son, Solomon, would succeed him as King (1 Kings 1:16-30). So, the dynastic succession would lawfully run through Bathsheba to Solomon. However, if Bathsheba had not received this promise, the dynastic succession would have run through Haggith to Adonijah, since Adonijah was older. So it was Solomon’s mother, Bathsheba, who provided Solomon with the lawful right to sit on the throne of David.

Now what would have happened if a power struggle took place and Adonijah became king? Adonijah would have deposed both Bathsheba and Solomon. We know why Solomon would be killed or imprisoned, but why Bathsheba? Bathsheba, by receiving David’s promise, became the tangible, living, guarantor of Solomon’s right to be king. That’s why Adonijah would have to depose both Solomon and his mother.

2. A Reflection of the King

The Queen Mother was a physical, tangible sign of the King’s legitimacy. Because of this direct link, how one viewed the Queen Mother had a direct bearing on how one viewed the King. If someone disrespected the Queen Mother, he was, through his actions, also disrespecting the King.

Why? What was the big deal? Such disrespect implied the King was not the rightful ruler. But if someone respected the Queen Mother, he also respected the King, showing through his actions that the king was the legitimate ruler and heir. That’s why paying homage to the King’s mother was a legitimate way (but not the only way) to pay homage to the King.

Now, if someone refused to honor the Queen Mother, such refusal was a negative criticism of the King. It could even be a way to criticize the King and his right to the throne. No loyal subject would refuse to honor the King’s mother, for to do so would be to dishonor the King himself.

3. An Intercessor for the King’s Subjects

Since the fate of the King and his mother were intertwined, the Queen Mother would naturally be the King’s trusted ally and advisor in the royal court. Rarely would a mother be so wicked and self-destructive as to choose to steer her son into a disaster. Simply put, such a move would not be in her self-interest. Because of this bond, the Queen Mother became a powerful advocate before the king for his subjects.

Those who hoped to make the king more disposed to answer favorably to their request would naturally ask the Queen Mother to present their petitions to the King (1 Kings 2:17, 2:20). Although the King would be inclined to answer his mother’s request favorably, it wasn’t a guarantee that he would always do so. The King could refuse, as he did with Adonijah (1 Kings 2:16-23). (Adonijah, a son of King David, wanted permission to marry King David’s last and youngest wife, Abishag as a way to try to gain legitimacy for the throne.)

4. A Minister under the King

The Queen Mother also had a share, just as all the officers and administrators under the King, in the King’s rule and administration of the kingdom. Jeremiah 13:18-20 reads:

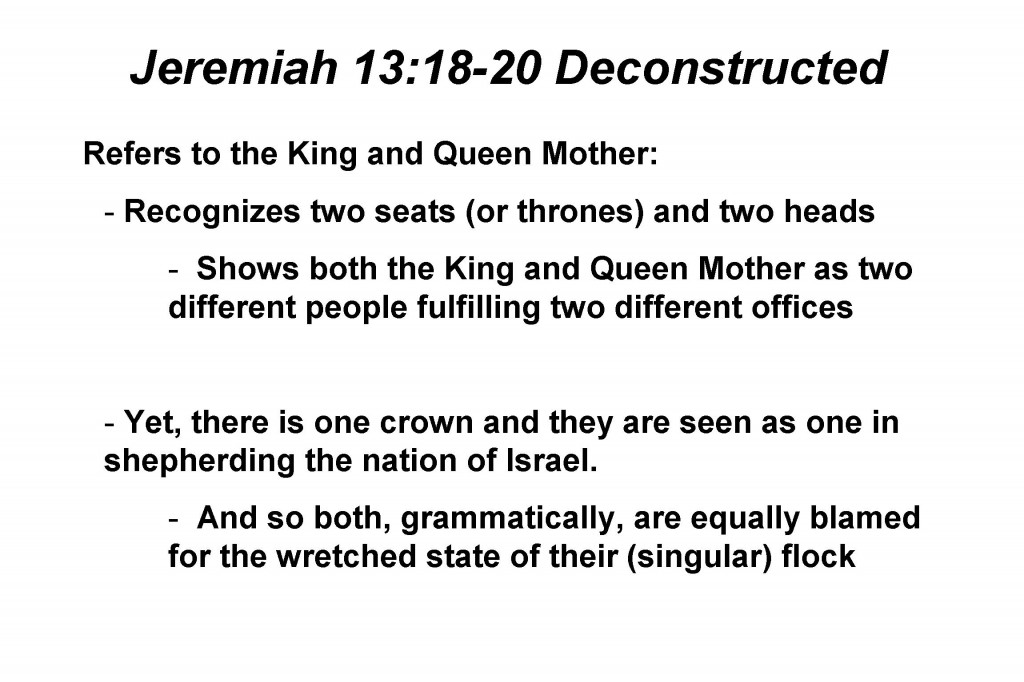

Say to the king and the Queen Mother: “Take lower seats, for your [singular] glorious crown has fallen from your [singular] heads. The cities of the Negev are under siege; no one can help them. All of Judah will be taken into exile, carried completely away. Lift up your eyes and see those who are coming from the north. Where is the flock entrusted to you [singular], your [singular] beautiful flock? [Jeremiah 13:18-20]

God’s words through Jeremiah show that the Queen Mother had authority in the kingdom while serving her son. For Jeremiah 13:18-20 used a singular “you” and “crown” when referring to both the King and the Queen Mother. So, although both held different offices and were two different people, the King and Queen Mother were viewed as one entity. And so they prospered and suffered as one. That’s why, grammatically, both the King and the Queen Mother are equally to blame for the poor condition of Israel.

Elsewhere in Scripture, we find a chapter containing the Queen Mother’s words through the hand of her son, the King. Proverbs 31 is a chapter by the Queen Mother of King Lemuel. And who was Lemuel? Ancient Jewish tradition says that Lemuel was a pseudonym for Solomon. If so, then Bathsheba was the author of Proverbs 31.

Queen Mothers in 1st and 2nd Kings

|

King |

Queen Mother |

Scripture |

| David | (New line of succession) | |

| Solomon | Bathsheba | 1 Kings 1:11; 2:13 |

| Rehoboam | Naaham | 1 Kings 14:21 |

| Abijam | Maacah | 1 Kings 15:2 |

| Asa | Grandmother Maacah | 1 Kings 15:10 |

| Jehoshapat | Azubah | 1 Kings 22:42 |

| Jehoram | (possible King co-regency?) | |

| Ahaziah | Athaliah | 2 Kings 8:26 |

| Athaliah | (?) | |

| Jehoash | Zibiah, | 2 Kings 12:2 |

| Amaziah | Jehoaddan | 2 Kings 14:2 |

| Uzziah (Azariah) | Jecoliah, | 2 Chronicles 26:3 |

| Joatham | Jerusa | 2 Chronicles 27:1 |

| Ahaz | Grandmother Jerusa? | 2 Kings 16:1-2 |

| Hezekiah | Abijah | 2 Chronicles 29:1 |

| Manasseh | Hephzibah | 2 Kings 21:1 |

| Amon | Meshullemeth | 2 Kings 21:19 |

| Joshiah | Jedidah | 2 Kings 22:1 |

| Jehoahaz | Hamutal | 2 Kings 23:31 |

| Jehoiakim | Zebidah | 2 Kings 23:36 |

| Jehoichin (Jeconiah) | Nehushta | 2 Kings 24:8 |

| Zedekiah | Hamutal | 2 Kings 24:18 |

Click here to go to Lesson 2: The Queen Mother: The New Covenant