The setting for The Parable of the Good Samaritan was a lawyer wanting to justify himself, asking Jesus to tell him “what he needed to do to inherit eternal life” (Luke 10:25). So, if you are someone who thinks he must do something to have eternal life, then you must be the “Good Samaritan.” Jesus commands you to “keep doing,” never to stop loving your neighbor—always, as an ongoing, continual action. This is an impossible, which is the point, which means you can’t do anything to have eternal life.

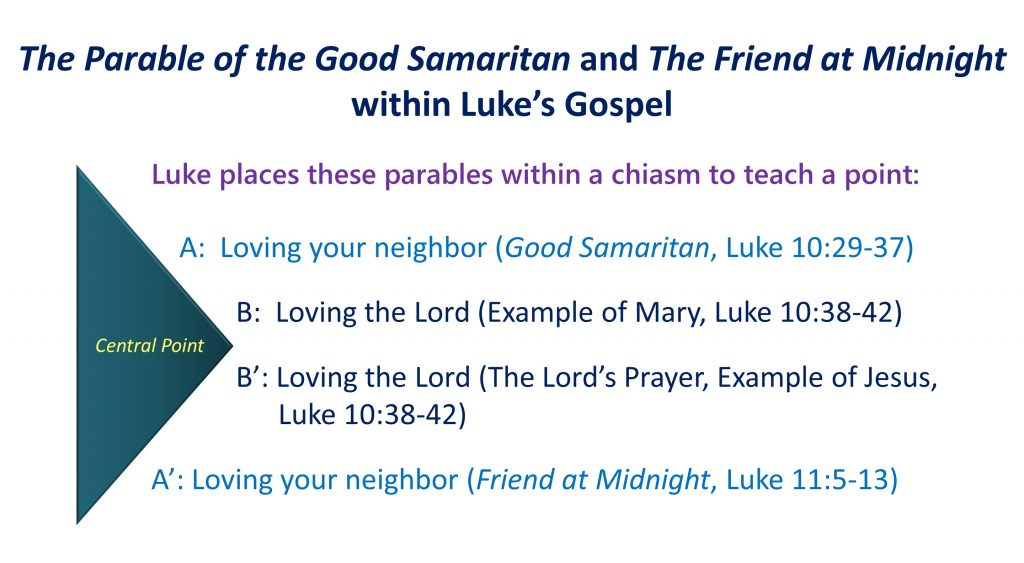

Within the flow of Luke, The Parable of the Good Samaritan moves the hearer from the lesser to the greater, from neighbor to God. Through a chiasm, Luke shows us loving your neighbor matters, but love for God supersedes all.

Jesus, Mary, and Martha

After The Parable of the Good Samaritan, we learn of the encounter between Jesus, Mary, and Martha.

Read Luke10:38-39

- Both Mary and Martha welcome Jesus. What is different about what Mary does?

“sat at the Lord’s feet”: To sit at the feet of a rabbi was the position of a disciple. For example, Acts 22:3 tells us Paul was instructed “at the feet of Gamaliel,” who was his teacher. The Mishnah (the Jewish oral traditions written down) confirms this: “Let your house be a place for the Sages and sit amid the dust of their feet and drink in their words with thirst” (Abot 1.4). What was considered shocking is Jesus allowing Mary to sit at His feet since rabbis did not have women disciples.

Read Luke 10:40

- What does Martha tell Jesus?

In 1st-century Jewish thinking, Martha actions were normal. For a woman did not presume to make herself a disciple of a rabbi, which Mary did by sitting at Jesus’ feet. Also, Jewish society considered service as a woman’s highest calling, which placed much value on hospitality.

Read Luke 10:41-42

- Why would Jesus’ response to Martha be shocking?

“Martha, Martha”: Jesus repeats Martha’s name, which is a way to show compassion or pity.

“good portion”: Jesus used a clever turn of phrase, normally reserved to describe a large amount of food. He took that expression and compared being taught in God’s ways to eating a filling meal. Spiritual eating is for eternal life; physical eating is for the here and now. That which leads to eternity “will not be taken away from her,” unlike the food we eat, which leaves us soon hungry.

- What does Jesus showing compassion on Martha reveal about her understanding of what’s important in the kingdom of God?

- Is Jesus implying serving one’s neighbor doesn’t matter? If not, what then is His point?

Before The Parable of the Good Samaritan, the lawyer condensed God’s Law as, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind, and your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:27). Jesus told him he was correct (Luke 10:28). So, if The Parable of the Good Samaritan deals with the commandment to love one’s neighbor, this episode with Mary and Martha deal with loving the Lord your God.

- Based on Jesus’ response, how is someone to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind”?

- Without “love for God,” what happens to one’s service his neighbor in the eyes of the Lord?

To love one’s neighbor is to be like the Good Samaritan—not to “do” something to have eternal life—but as a response of faith. To love God means to be like Mary. These are two characteristics of the Christian. To receive from the Lord and to give to others (with service to others being implied because the context Jesus dealt with was “works righteousness,” not “license to sin”). Without love for God, the service for others does not merit anything in God’s eyes.

The Lord’s Prayer

Read Luke 11:1

- What does Jesus’ disciples imply when they ask Him to “teach us to pray”? In other words, what does this mean in contrast to “teach us how to pray?”

Read Luke 11:2

“say”: legete, an imperative, present active. Jesus commands His prayer as an ongoing prayer for the Christian all his life (present active). This never becomes “vain repetition” (an unfortunate translation from the KJV, better translated as “babble”), a phrase Jesus used to describe pagan prayers. “When you pray, do not babble as the Pagans do,” after which He gave to them His prayer (in Matthew’s Gospel).

“Father”: father, Greek, pater; Aramaic, abba. Abba, was an intimate term, which Jesus used to address God (Mark 14:36). 1st-century Jews would sometimes refer to God as “heavenly Father,” but rarely (or never) as “father,” abba.

- Jesus commands His disciples to call God, “Daddy.” Why can we use such an intimate term, which was restricted to the immediate family.

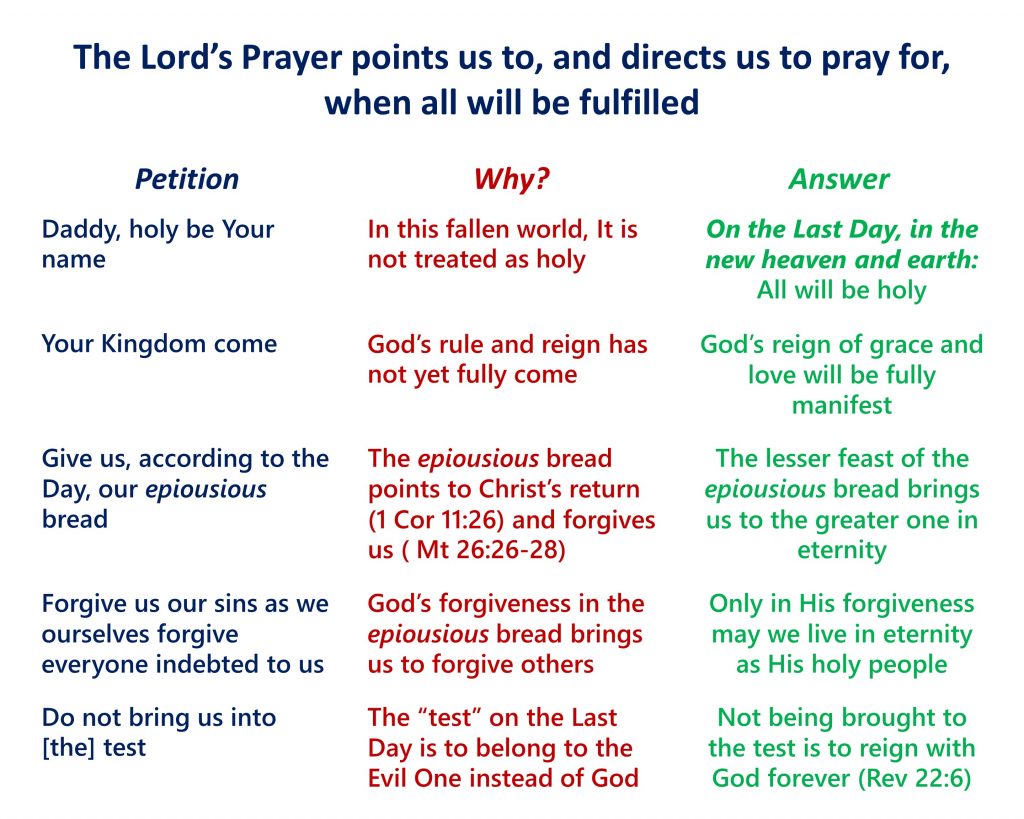

“hallowed be”: imperative passive. Jesus commands us to pray for His Father’s name to be holy, though we have no ability to make it holy. Thus, what Jesus commands of us, God must do—which is the point!

- What does this reveal about worship and prayer, if we do can nothing to make God’s name “holy”?

“Your kingdom come”: come, eltheto, aorist, active. This shows God’s kingdom, His rule and reign, are the result of what He does, which the prayer Jesus gives is to teach us to recognize.

- So, if we can do nothing to make God’s name holy, how is comforting to know His rule and reign are the result of what He does?

Read Luke 11:3

Excursus: “Daily Bread”

“daily”: epiousious, an extremely rare, compound word. This word is comprised of “epi” in the accusative case, meaning direction to or toward something, and “ousious,” meaning substance, essence, or being. The adjective epiousious changes the “bread” into something which directs the one praying toward some substance or essence or being.

Right now, this is as clear as mud, made worse by finding no other examples of this word in Jesus’ contemporary Greek language! Origen (186-255 AD, North African Bishop) said he could find no example of epiousious from other Greek writers (On Prayer 27:7). “We should consider the meaning of epiousios. First of all, we should note the word epiousios is not employed by any of the Greek writers, philosophers, or individuals in common usage …”

So, Origen looked to the Greek-language Old Testament (Septuagint) for guidance.

An expression of great similarity to epiousios is found in Moses’ writings, as spoken by God: “You will be my particular (periousios) people” (Exodus 19.5). It seems to me that each of these words is derived from the word “essence” (ousia). The first [periousios] signifies the proximity of the people to the essence and their participation in it; the second [epiousios], denotes the bread that is conjoined with the divine essence. [On Prayer 27.7]

Origin saw the petition for “epiousios bread” as a confession of the Supper Jesus would institute and His divine presence in it.

- Discuss: In the Liturgy, why does the Church usually put the Lord’s Prayer before the Words of Institution?

The Latin Vulgate translator, Jerome (347-420 AD), said the Hebrew-language Gospels understood epiousios as referring to the food of the messianic banquet awaiting God’s people in eternity. Since “Your kingdom come” ultimately points to God fulfilling all in the new heaven and earth, this lends credence to Jerome’s conclusion.

Your pastor understands that when we pray for “epiousious bread,” we are confessing our faith in the being (ousious) of Jesus being present with us in His Supper. Jesus gives us to pray, “Give us according to the day our epiousious bread.” “The day” is ambiguous, which could mean “today” or even “the Last Day.” Since the previous petition dealt with “Your kingdom come,” the Last Day fits the context.

Thus, Jesus directs us toward (epi) the essence and being of Himself (ousious) in the bread (artos) of His Supper. This, in turn, directs us toward the Last Day. As the Apostle Paul wrote: “Whenever you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Corinthians 11:26)

“Epiousious bread” directing us to our Lord’s Supper makes sense. For Jesus commanded, “Take, eat; this is my body…. Drink of it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for the many for the forgiveness of sins (Matthew 11:26-28). The next petition deals with forgiveness of sins.

————

Read Luke 11:4

The first “forgive”: aphes, an imperative. Jesus commands us to command God to forgive our sins.

The second “forgive”: aphiomen, a present active.

This is not conditional. In the first “forgive,” we command God to forgive us (which is okay since Jesus commands this). In the second, we pray for an ongoing ability to forgive the sins of those who “owe” us, meaning those who are not forgiving us as they should. Otherwise, they would not “owe” us.

“temptation”: peirasmos. Not so much “temptation” but being tested or tried.

The entire prayer is the prayer of a community, not the individual: “Give us” “our bread,” “forgive us” as “we forgive,” “lead us,” and “deliver us.”

- What does this tell us about the nature of who we are in Christ and how this manifests itself:

- in how we live,

- how we pray,

- and for what we seek?

The entire Lord’s Prayer is primarily eschatological, pointing to the time when Jesus will return. God’s kingdom will come on the Last Day. The “epiousious bread” directs us to this event, through which God forgives us. Since He forgives us (how can He not since Jesus commands us to command Him to forgive us), we forgive others. Only in forgiveness are we not led into trial but delivered from the Evil One.

We now segue from loving God (the example of Martha and praying the Lord’s Prayer) to the parable closing the chiasm: The Parable of the Friend at Midnight. Scripture often shows God coming to His people to deliver them at midnight. In the Old-Testament account of God’s rescue, He said He would go among the Egyptians at midnight (Exodus 11:4), which He later did (Exodus 12:29) to deliver His people.

The Psalmist prayed, “At midnight, I rise to praise you because of your righteous judgments” (Psalm 119:62). Here, the two times coincided, when God made his “righteous judgments” known and praising Him for them.

The New Testament, in another parable, pictures Jesus returning on the Last Day as a groom coming to meet his bride … at midnight! (Matthew 25:6). So, our Lord doing His work to rescue His people is often pictured as taking place at midnight. So the parable’s setting, following the Last-Day focus in the Lord’s Prayer matches well.

The Parable of the Friend at Midnight

Read Luke 11:5-6

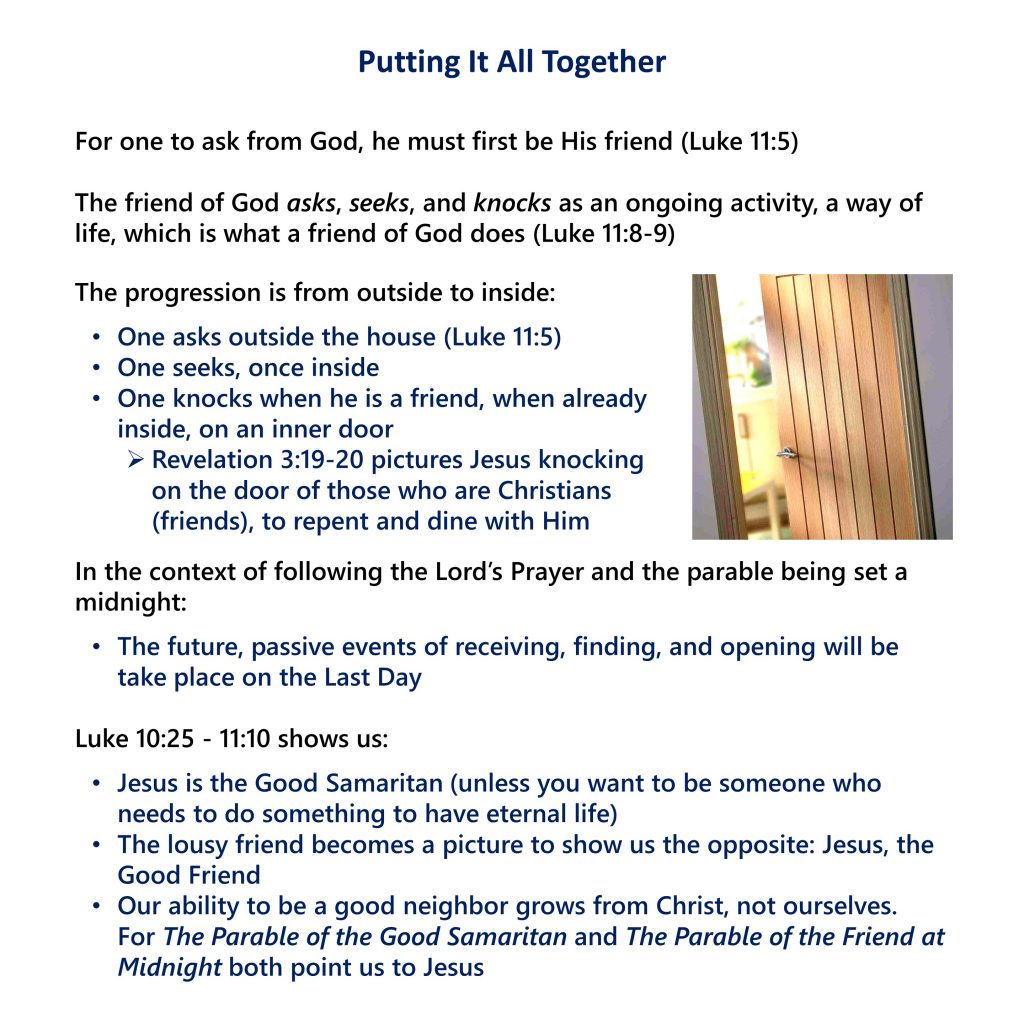

Only strangers knock on doors at night in the Middle East. The host in this parable goes to his neighbor and calls—he does not knock (Luke 11:5-6). A knock will frighten his sleeping friend, while a recognizable voice will assure those in the house that no foul play is afoot.

- A friend asking for food at midnight implies what about being able to get it elsewhere?

- Though inconvenient, what will a friend do, if he’s a real friend?

Read Luke 11:7

- How does this “friend” respond?

“I cannot get up and give you anything”: Literally, “I am not able [do not have the power or ability] to get up to give you.” The verse doesn’t say what he is unable to give, only that he claims he doesn’t have the ability to get up and give. So, the focus is not on what the person in the house doesn’t have but that he is too weak to get up and give. The answer is absurd.

Read Luke 11:8

- What do we learn eventually happens?

- Why?

“impudence”: anaideia, shamelessness linked with persistence, a shameless pestering. This person keeps on asking and persisting to the point of becoming obnoxious. The man inside knows he will get no peace until he gives his friend some food.

Read Luke 11:9-10

- In the verses, who is the person addressing when he is his asking, seeking, and knocking?

- According to the context of the parable, before someone may “ask,” what does he need to be to the one he is asking? (vs. 5)

- Thus, if a mediocre friend provided for his friend, what does this imply about God and/or Jesus?

| Action | Result |

| “ask”: a present, active, an ongoing state of being | “will be given”: a future, passive. You will receive that for which you have asked … in the future. This isn’t because you have asked (the passive voice) but because of the One who gives |

| “seek”: a present, active, an ongoing state of being | “will be found”: a future, passive. You will find that for which you have sought … in the future. This isn’t because you have sought it (the passive voice) but because of the One who finds it for you |

| “knock”: a present, active, an ongoing state of being | “will be opened”: a future, passive. The door you knock on will be opened … in the future. This isn’t because you knocked (the passive voice) but because of the One who opens it |