The Parable within Luke’s Gospel

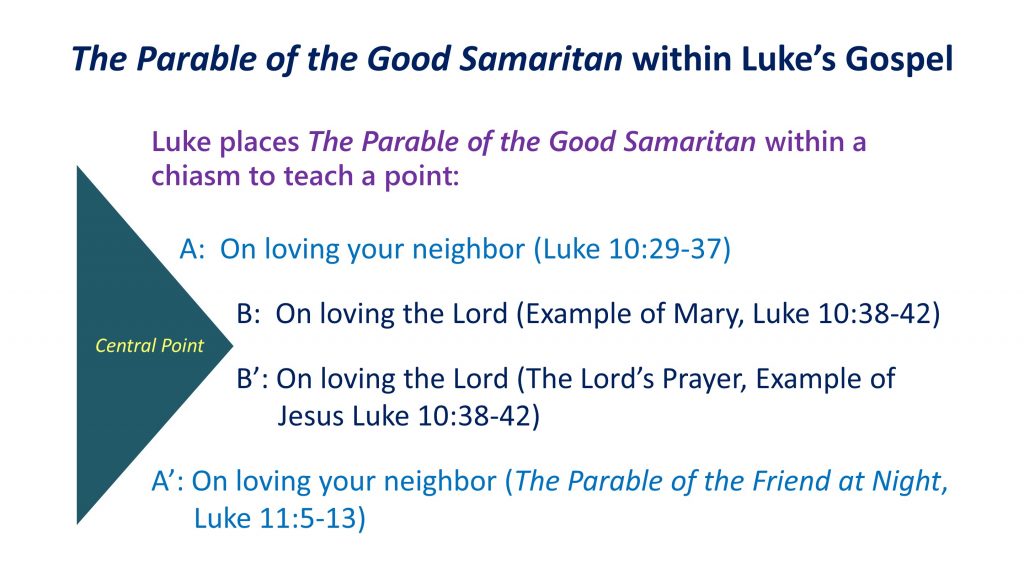

If we remember, we learned a chiasm is a rhetorical device where the author states an idea or ideas and then expresses them again in reverse order. The central point of a chiasm is its central idea.

Within the flow of Luke, The Parable of the Good Samaritan moves the hearer from the lesser to the greater, from neighbor to God. Yes, loving your neighbor matters, but love for God supersedes all.

Far from a patchwork of sayings and stories, Luke weaves them together by the Spirit’s inspiration. An entire section joins two parables together, started by a lawyer’s question. The end of this section is also a parable, which at first seems different. The Parable of the Friend at Night appears to focus on prayer. But both within the flow of Luke’s Gospel deal with loving the Lord and loving your neighbor.

- Of the two, loving neighbor and loving God, which is more “central”?

- Discuss why.

The Structure of the Parable

The parable consists of parallel questions and responses, one following the other. The ideas of “neighbor” (vs. 27, 36) and “do” (vs. 25, 28, 37) connect the two parts.

| Part One | Part Two |

| 1. The lawyer’s question (vs. 25)

· “What must I do?” |

1. The lawyer’s question (vs. 29) |

| 2. Jesus’ counter-question (vs. 26) | 2. Jesus’ counter-question (vs. 30-36)

· “Who … proved to be a neighbor…?” |

| 3. The lawyer’s answer (vs. 27)

· “… love … your neighbor as yourself.” |

3. The lawyer’s answer (vs. 37a) |

| 4. Jesus’ command (vs. 28)

· “Do this, and you will live.” |

4. Jesus’ command (vs. 37b).

· “Go and do likewise.” |

Read Luke 10:25

- What informs us the lawyer does not really want to learn what Jesus has to teach?

“lawyer”: This does not mean what we think “lawyer” means. Unlike our culture, “lawyer” did not come with negative connotations. Nomikos, “lawyer,” was also a synonym for a “scribe,” grammateus. This man was an expert in the Old-Covenant Law.

“test”: is similar to the other trick questions Jesus’ opponents posed to Him. The trick question is one that cannot be answered “yes” or “no” without getting in trouble.

- “Is it lawful for us to pay taxes to the emperor?” (Luke 20.22). To respond “yes” invites the accusation that one is a collaborator. To respond “no,” that one is a revolutionary.

- The Sadducees asked Jesus a trick question. They adapted the story of Tobit about a woman married to seven brothers, who all died, one after the other. Whose wife is she in the resurrection (Luke 20:29-32)? Because the Sadducees did not believe Tobit to be Scripture or in the resurrection, the question was hypothetical, meant to ensnare.Fromthe Greek, ekpeiradzo, “test” is what Jesus’ followers pray to avoid: “Lead us not into temptation.” The petition in the Lord’s Prayer, is literally, “Do not bring us to the test [the noun form]” (Luke 11.4). It’s no coincidence that Jesus gives His prayer to His disciples a few verses following The Parable of the Good Samaritan!

“do”: Here, the lawyer used an aorist participle (poesas), a “tense” pointing to a single, limited action. The lawyer is thinking of something to check off a to-do list: recite a prayer or offer a sacrifice. You do a one-time deed and move on to whatever’s next.

“inherit”: The lawyer’s original question is flawed. (So bad questions do exist!) What can anyone do to inherit anything? Nothing. An inheritance is a gift from one family member to another when someone dies. An inheritance isn’t a payment for services rendered. The lawyer knows this. So, he asks a “trick question” that someone can’t properly answer: one does not “do” anything to “inherit” eternal life.

The Jews in Jesus’ day did think they needed to “do” something to merit eternal life. However, a sincere question, would not have used “inherit.” Around 90 AD, Rabbi Eliezer reported his students asking him, “Rabbi, teach us the ways of life so, by them, we may attain [not “inherit”] the life of the future world.”

Read Luke 10:26-28

- By Jesus’ counter-question, what does He “force” the lawyer to do with his own question?

By His counter-question, Jesus implies, “Surely, you know the answer; after all, you’re the expert.” But Jesus begins to lay His own snare with “How do you read it?” In other words, is your “interpretation” the same as God’s “interpretation”?

- Did the lawyer understand and condense the meaning of the Law correctly?

- How does Jesus “give” and “take away” by His two-part statement: “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live”?

“Love God and Neighbor”: Two Old Testament texts, Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18, contain the first and second greatest commands. Both commandments held a prominent place in Jewish thought. The command to love God was constantly before the Jews as they recited the daily prayer known as the Shema: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. Love the LORD your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength” (Deuteronomy 6:4-5).

The lawyer correctly ranks love for God and neighbor, with God coming first. Still, he doesn’t realize the implication that one’s ability to love his neighbor is linked with his love for God.

“do”: Earlier, the lawyer earlier used an aorist participle (poiesas) for “do,” a “tense” pointing to a single, limited action. Jesus uses an imperative, present, active (poiei)—commanding the lawyer to be loving God and neighbor always, as an ongoing action, if he wants to “do” something to “inherit” eternal life!

- Discuss: If one cannot do anything to receive an inheritance, why does Jesus tell the lawyer to “do this [love God and neighbor], and you will live”?

Read Luke 10:29

- What does the lawyer, “desiring to justify himself,” reveal about what his own question is doing to him?

“neighbor”: plesion, an adjective, meaning “nearby,” “close,” or “beside.” When combined with an article, it becomes “the one nearby” or “the one beside.” In the Greek-language Old Testament (the Septuagint), “neighbor” describes, not only people related by blood or religion, but also those who are not. A neighbor is someone brought into your life as you go about your everyday tasks. So, even the Jews of yesteryear understood that “neighbor” could transcend blood and tribal relations.

- What is the lawyer trying to do by getting Jesus to specify who his neighbor is?

Jesus Responds with a Story

Read Luke 10:30-32

“going down from Jerusalem to Jericho”: An actual descent, which Jesus also makes figurative, as a picture of spiritual decline to describe the Priest and Levite. This was a desolate 17-mile road, dropping from over 2,500 feet above sea level in Jerusalem to around 800 feet below sea level at Jericho. The route could be dangerous, with many places for robbers to lie in wait for unprotected travelers.

- What did both the Priest and Levite do?

“Priest”: A Levite, but more specifically a descendant of Aaron, the brother of Moses and first priest of Israel (Exodus 28:1-3). God entrusted priests with the spiritual oversight of the nation, including teaching the Law (Leviticus 10:11, Deuteronomy 17:18), administering the Temple and the sacrificial system, and inspecting uncleanness, especially leprosy, in the people (Leviticus 13-14).

“Levite”: A descendant of Levi, one of the twelve sons of Jacob (by Leah). They were not given an allotment of land (Numbers 35:2-3; Deuteronomy 18:1, Joshua 14:3) to earn an income. So, they lived from the tithe as they assisted the priests in the service of the tabernacle (Numbers 18:4) and Temple.

Touching a dead body rendered priests and Levites ceremonially unclean and unable to fulfill Temple commitments (Leviticus 21-22). Even more, Jewish thinking understood the impurity of a corpse traveled upward through the air. So, if any part of the Priest’s or Levite’s body leaned over a corpse, he would become impure. This explains why they both made a wide berth around the suspected corpse.

In this story, Jesus forces the lawyer to wrestle with which Mosaic Law should prevail: The need to avoid defilement by a (suspected) corpse or the obligation for one Israelite to help another in need.

Read Luke 10:33

“Samaritan”: In 722 BC, the Assyrians captured the Northern Kingdom of Israel, deporting most of the population, who lost their identity living among other peoples. The Assyrians deported people from other vanquished nations into Northern Israel who, over time, became the Samaritans. Their religion became a mixture of Judaism with others religions, becoming its own. The Samaritans later opposed the efforts of Ezra and Nehemiah to rebuild Jerusalem (after the Babylonian exile of the Southern Kingdom) (Ezra 4:1-4; Nehemiah 2:19, 4:1-5), building a rival temple on Mount Gerizim. In Jesus’ day, some rabbis taught that if a Samaritan accepted alms from a Jew, that would delay the redemption of Israel!

- Unlike the Priest and Levite, why is the Samaritan “free” to go to where the (suspected) dead man was?

- What seed does Jesus plant in the back of the lawyer’s mind about the Old Covenant?

- What stirs within the Samaritan, which is left unstated about the Priest and Levite?

The implication is the Priest and Levite did not have compassion, and so they did not act. The Samaritan did. So, did his compassion have anything to do with how he acted? If not, the Samaritan’s compassion will be irrelevant, and like the Priest and Levite, he will do nothing. But if the Samaritan’s compassion was relevant, then he will act. So, with the lawyer, we are now drawn deeper into the story, wondering what the Samaritan will or will not do!

Read Luke 10:34-35

“oil and wine”: Oil and wine had medicinal value (Isaiah 1:6), with the oil serving as a balm and the wine as a disinfectant.

“two denarii”: two day’s wages. This would cover the bill for food and lodging for at least a week, perhaps two.

- What did the Samaritan do?

What we might miss is this: When the Samaritan takes the wounded Jewish man to a Jewish inn, he risks his life to care for him. In the end, Jesus does not answer the lawyer’s question, “Who is my neighbor?” Instead, Jesus reflects on the larger question, “To whom must I become a neighbor if I need to ‘do’ something to ‘inherit’ eternal life?”

The Implications of the Parable

Read Luke 10:36-37

- What does Jesus ask the lawyer?

- How does the lawyer refer to the Samaritan? What does this reveal?

“mercy”: The lawyer brings up the word “mercy” (eleos), earlier Jesus used “compassion” (splagchnizomai). Mercy is being treated as one does not deserve.

- What does Jesus tell the lawyer to “do”?

“do”: Like before, the lawyer this time referred to what the Samaritan did as a one-time action in the past. Jesus again uses an imperative, present-tense verb—“keep doing.” The lawyer doesn’t get it: he keeps using one-time, past-tense verbs, but Jesus commands him to keep loving God and neighbor as an ongoing action—if he wants to “be doing” enough to “inherit” eternal life. A neighbor now includes Samaritans, not just Jews. Even if one’s neighbor only included one other person, the “keep doing” aspect of what Jesus commands makes this impossible to do.

Within the Law, the lawyer’s question of “who is my neighbor” has legal merit. Someone does need to know who are neighbors and who are not. Not so in the context of love. Love makes his question irrelevant.

Excursus: Who is the Good Samaritan?

The answer depends on whether your eternal life depends on what you do. If eternal life depends on what you must “do,” you must always be loving God and neighbor and never not be doing so. This is impossible, for we cannot be fully on, always doing this commanded task from Jesus. And Jesus means for it to be an impossible task—revealed by the verb tenses He used and ensuring you understand who your neighbor is.

If you are like the lawyer, then Jesus commands you to be the good Samaritan, and your neighbor is the man left for dead in the ditch. If you want to be right with God based on what you “do,” Jesus will always give you something you can’t do—always!

If you are to do the works needed to earn eternal life, love the man in the ditch. Whomever God places in your path (the real meaning of “neighbor”), no matter the personal cost or inconvenience, love him! Now, this goes beyond inconvenience, beyond hurting, into the realm of impossibility. Ask a Law question, and you will receive the Lawman’s answer.

If, however, eternal life for you is not by your doing, but by inheriting (the real meaning of “inherit”), then you are not the Good Samaritan. Eternal life happens because you belong to the right family, whose father ensures he leaves you an inheritance, which you did not, and could not, earn or deserve. Who then do you become in the parable? You are the man left for dead on the side of the road.

The irony is the lawyer’s use of bringing in the word, “mercy.” This unintended word by the lawyer becomes the linchpin to understand what the Samaritan does within the flow of Luke’s Gospel. Almost every instance of “mercy” in the Gospel of Luke is associated with what God does, including what He does through His Son. (See Luke 1:47-50, 54, 72, 78; 17:13; 18:38-39.) The lone exception is when Father Abraham refuses to show the rich man “mercy” (Luke16:24), which ironically proves the rule that in Luke’s Gospel, only God and Jesus show mercy!

Within the immediate context of Luke’s Gospel, the Good Samaritan, who shows compassion and has mercy, functions as a “Christ” figure, acting as God’s agent. In Jesus, God became our neighbor. He joined us in the ditch, where sin left us for dead. The Word became flesh to live among us, to be God with us, and to fulfill the Law for us. He frees us from the burden of the Law. Christ became our neighbor, embracing us in our death.

Jesus heals our wounds with His wounds, applying the healing wine and oil of His Word and His body and blood to restore us. He forgives and frees us from the Law. This is The Parable of the Good Samaritan. If Christ is not the doer for us, then we are not wearing Jesus’ glasses and understanding the parable.

Only after we are freed from the Law, are we then free to do the Law: Love God and love our neighbor. Why? Only when you are freed from having to be good enough, can you do something to please God. With Christ as your righteousness, you can’t lose!

Jesus frees you from the Law by fulfilling it, allowing you to act like the Samaritan, who is free of the Mosaic Law. Since you get your purity from Jesus, you can respond in compassion, even getting yourself dirty as you serve your neighbor. Until we believe “no condemnation now exists for those in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1), we will never be free. Until we realize “Christ is the end of the Law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Romans 10:4), we will never have the Samaritan freedom to love others in need. Without the freedom that comes in Christ, we will not love God and others without becoming resentful.

If you have given up on yourself trying to earn God’s favor, then the Law has done its work. What must you do to “inherit” eternal life? Nothing. For an inheritance is received, not earned! This the lawyer never figured out. You receive an inheritance because you were born from above into the right family, God’s family, in the waters of holy baptism.