Paul, through a scribe he used, named Tertius:

- [From] Paul, a slave of Christ Jesus… (Romans 1:1)

- I, Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord (Romans 16:22).

Paul normally used a scribe, like Tertius. The cost of producing a letter of exceptional length, like Romans, was expensive. A scribe could simply transcribe, suggest ways to shorten what was said, and write using smaller letters, which were still legible.

Paul used a scribe, often a pastor, who sometimes co-wrote a letter with him. Tertius was also a pastor in Iconium (today, in Turkey). What we don’t know is what editorial role he may have taken. When Paul did physically write the letters, most often it was the closing greeting, which we find in 1 Corinthians 16:21-24, Galatians 6:11-18, and Colossians 4:18.

The Church at Rome: The Jews

We don’t know how or when the Christian Church first formed in Rome. We do know “visitors from Rome” (Acts 2:10) were among the Jews on Pentecost Day, but neither Romans nor Acts tell us of any missionary or Apostle who brought the Word of Christ to Rome. So, lacking anything to the contrary, sometime after Pentecost would be the best time to date the beginnings of the Church at Rome. If so, the Church, then, would be comprised mostly of Jews who believed in Jesus as the Messiah.

In Romans, we find internal evidence of Jews being part of the Church there. Paul, in:

- 2:17-3:8, deals directly against a Jewish speaker.

- 3:27-31, defends himself against Jewish objections that his teaching about justification by faith sets the Law aside.

- 4:1, refers to Abraham as “our forefather according to the flesh.”

- Chapters 9-11, finds it necessary to defend the role of Israel in God coming to save humanity.

- isolated verses, such as 6:16, 8:15, 9:1-5, 10:1-2, and 15:26, implies Jewish Christians are on the receiving end of his letter.

- 16:7, Greets Andronicus and Junia as “my fellow countrymen,” that is, as Jews.

Ambrosiaster, who wrote a commentary on the Apostle Paul’s letters, around the 370s, said this:

It is evident then that there were Jews living in Rome … in the time of the Apostles. Some of these Jews, who had come to believe (in Christ), passed on to the Romans (the tradition) that they should acknowledge Christ and keep the Law.… without seeing any signs of miracles and without any of the Apostles they came to embrace faith in Christ, though according to a Jewish rite” [Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, 81.1.5-6].

The Church at Rome: The Gentiles

In Romans, we also find internal evidence of Gentiles also being part of the Church there. Paul, in:

- 11:13, refers to himself as “the Apostle of the Gentiles” and addresses his readers as “Gentiles.”

- his opening paragraphs, includes the Roman Christians among “the other Gentiles” (1:13, see also 1:5-6 and 15:15-16).

- 9:3-4; 10:1-2; and 11:23, 28, and 31, speaks to Gentile Christians about his own people.

- 6:17-22, recalls to the Christians at Rome their former sinful lives as heathens.

- 12:1-2, implies a Gentile background of the Roman Christians.

Ambrosiaster also spoke of Gentile Christians at Rome, who were associated with the original Jewish converts of the Church at Rome.

The “Chrestus” Problem

Early on, the Roman authorities did not understand or realize that Christianity was different from Judaism (or was Judaism fulfilled). If they realized anything at all, it was that Christianity was a sect within Judaism, and thus still a legal religion in the Roman Empire.

As the Church grew in Rome, a ruckus broke out among the Jews about someone named “Chrestus.” The authorities didn’t know who this Chrestus was, so they could not arrest him to restore the peace. Romans historian, Suetonius (69-after 122 AD), recorded, “The Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of ‘Chrestus.’” So, frustrated, Emperor Claudius (Emperor, 41 to 54 AD) expelled all Jews from Rome. Chrestus, however, wasn’t the name of a Jewish agitator living in Rome but a careless spelling of the name “Christus,” Christ.

Paul Orosius, a Christian pastor and historian (375-after 418 AD), dates the expulsion of the Jews to 49 AD. We also know Claudius’ expulsion of all Jews from Rome also included the Jewish Christians. After the expulsion, Paul met “a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, who had recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had ordered all the Jews to leave Rome” (Acts 18:2).

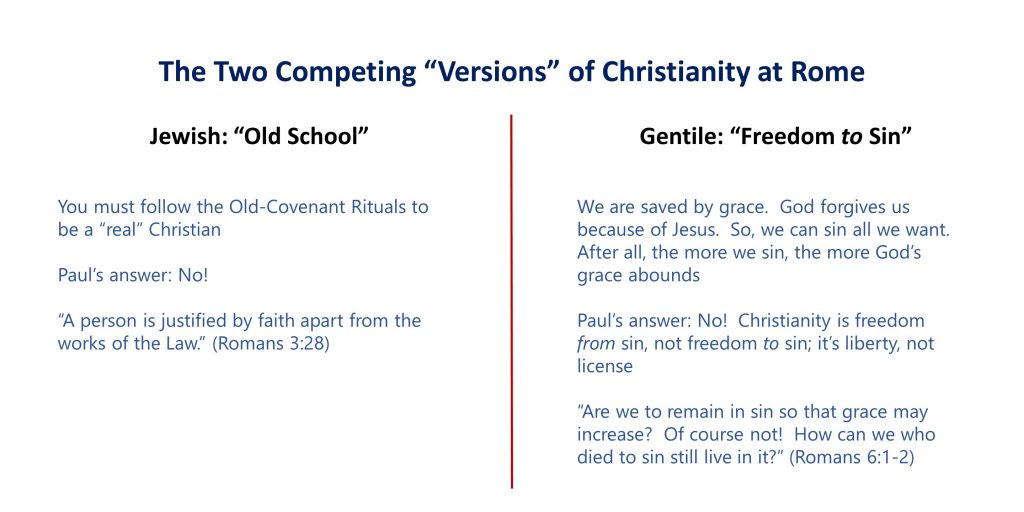

Competing “Versions” of Christianity

After 49 AD, the Christian Church in Rome became fully Gentile. They are now “in charge,” no longer the outsider but the establishment. After 54 AD, when Emperor Claudius died, the Jews begin to return. By now, however, the “balance of power” has shifted and two competing versions of Christianity vie for dominance. Although the Jews are now outnumbered, they have the “street cred” of being God’s Old-Covenant people and knowing the Scriptures better. In Romans 16, among the names Paul mentioned, we find 18 Greek names, 10 Latin, and 2 Hebrew.

We see Paul dealing with these “versions” of Christianity even in his use of the Old Testament (then the Scriptures). When dealing with the Jewish “problem,” we find many allusions, quotes, and echoes of the Old Testament: Romans 1-4:25 and chapters 9-11. With the Gentile “problem,” we find almost no direct references, for example, Romans 5:1-8:39, even though he did use the Old Testament in this section with broad brush strokes.

Date

When Paul wrote Romans, he was staying at the house of Gaius (Romans 16:23). Gaius was someone whom Paul baptized at Corinth (1 Corinthians 1:14). In his letter, Paul tells the Romans that Macedonia and Achaia (the northern and southern Roman provinces of Greece) decided to contribute to the collection he will soon bring to Jerusalem (Romans 15:26). This lets us know that the conflict between Paul and the Corinthian Church, which was a reason he wrote 2 Corinthians, was now resolved.

This dates Paul’s letter to Rome to the winter of 56-57 AD. We find further corroborating evidence for this in Acts 20:1-6: Paul was staying in Greece (Achaia, where Corinth is located) for three months (Acts 20:3) before sailing for Syria from Philippi, after the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Acts 20:6), which was later during Spring. It was during this hiatus of three months in Corinth when Paul wrote to the Romans in the winter of 56-57 AD.

Purpose of Romans

First, Paul wants to settle the controversy between the Jewish and Gentile Christians at Rome, mentioned earlier. Second, Paul wants to visit the Christians at Rome (Romans 1:13) but the demands of his work in the East (today, Greece and Turkey), which had kept him from doing so (Romans 15:17-19, 22). Now that he has completed his missionary work in the East, he wants to begin mission work in the West, in Spain. So, Paul plans to visit Rome and then go to Spain (Romans 15:24).

But first, Paul needs to bring the collection to Jerusalem (15:25-29), still the “mother Church.” Paul goes to Jerusalem and is arrested and imprisoned in both Jerusalem and Caesarea (Acts 22-26). However, when he appeals to Caesar because he is a Roman citizen, he gets transported to Rome as a prisoner (Acts 27-28). There, he remained under house arrest for two years (Acts 28:30-31), which is where the book of Acts ends. While there, under house arrest, Paul becomes the acting bishop of Rome.

Paul gets released and goes to Spain. “[Paul] taught righteousness to the whole world, having reached the Western boundary [Spain]” (1 Clement 5:7). But before he leaves, in your pastor’s opinion, he petitions Peter to come and serve as bishop. Based on the Jew-Gentile divide, who was better qualified to come and help resolve the issue than Peter? He had a reputation as the Apostle for the Jews. So, Peter came to Rome and served as bishop there, until he was martyred in 64 AD, becoming the first official Pope for the Church of Rome.

Petitioning Peter to come makes even more sense since Paul considered the Jewish viewpoint as more dangerous than the Gentile error. We know this because Paul only makes a supplemental appeal to the Jewish Christians, not the Gentile ones (Romans 16:17-20): “your obedience is known to all.”

Paul’s Use of Greek and the Old Testament

Cicero (Roman, 106 – 43 BC) wrote that, although knowledge and use of Latin were not uncommon in the Roman Empire, its use and influence was less than Greek. “If anyone thinks that the glory won by writing Greek is less than that given to the one who writes in Latin, he is entirely wrong. For Greek letters are read in almost every nation there is, whereas Latin letters are confined to their own, quite narrow, boundaries” (Pro Achaia, 23). So, even in Rome, using Greek made the best sense.

Even more, the Scripture of Paul’s day was the Septuagint, a Greek-language translation of the Old Testament, both for Jew and Gentile. So, it would make sense for Paul to write in Greek, the lingua franca of the Roman Empire, instead of Latin, the language of government. It was not until the 180s AD that Christian writers in the West began to write in Latin, beginning with Apollonius (died 185 AD) and Victor of Africa (later Pope, 186-198 AD).

Paul was raised as a Jew, “a Pharisee’s Pharisee” (Acts 23:6) and a student of Gamaliel (Acts 22:3), who was the grandson of the Hillel, one of two schools of thought for the Pharisees of the 1st century. The other was the school of Shammai.

Thus, unless his understanding of what books made up the Old Testament had changed, Paul would have viewed the entire Septuagint as Scripture, which included the books of what we call the “Apocrypha.” And that is what we find: Paul quotes, alludes, and refers to book throughout the Septuagint.

He referenced the Torah, pointing back to Adam (5:12-21), Abraham (4: 1-25), the patriarchs (9:6-13), Moses, and Israel’s exodus (9:1-5, 14-18; 10:5-8). He also used Kethuvim, “the Writings,” in his use of the Wisdom of Solomon when dealing with idolatry (1:18-31). Paul alluded to Job in 11:35, providing an important clue to his argument. He pulled from the Psalms, illustrating the sinful character of humanity (3:13-18) and God’s gift of Righteousness (4:7-8)—even to the Gentiles (15:9-12). And Paul pointed to the suffering Christ had already experienced (15:3) and currently being experienced by Christians (8:36).

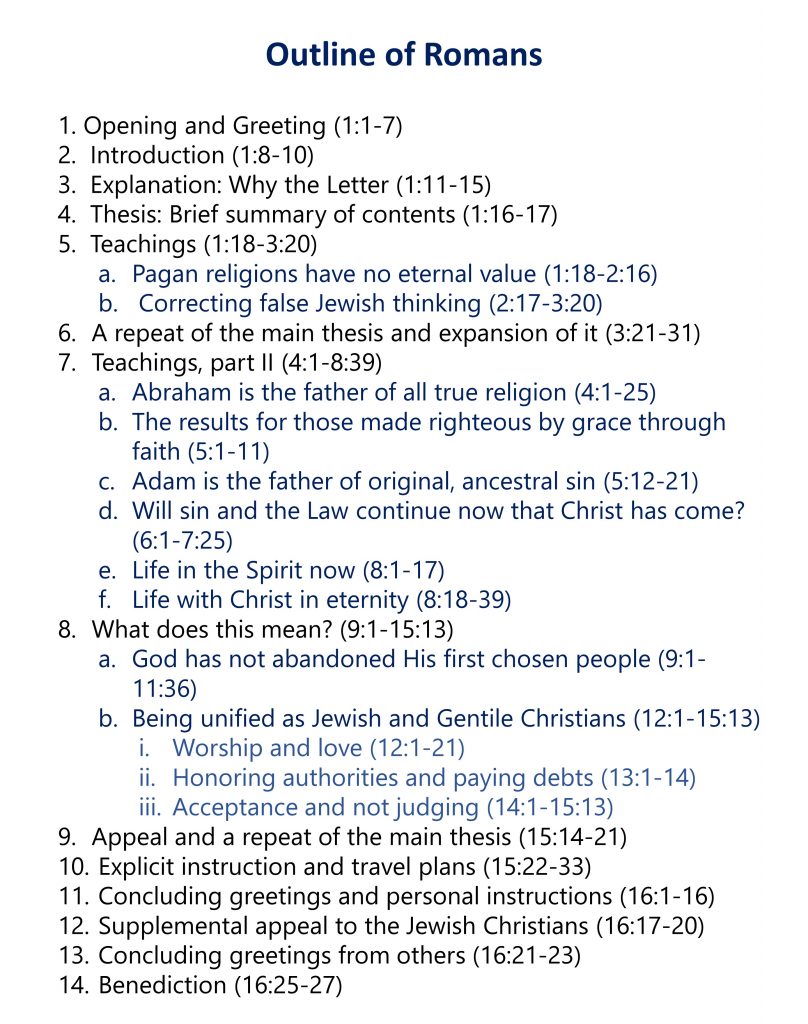

Outline

Biblical scholars have not reached any consensus in identifying a specific rhetorical style or literary format that Paul used for Romans. So, to provide an outline to help us see a structure within Romans, your pastor has approached Romans, first, as a letter to resolve the disunity between the Jewish and Gentile Christians. From such a viewpoint, here is the outline.