After taking a look a one-lesson excursion on what it means to praise God, we again approach the topic of prayer. Today, we examine the topic of praying for those who have died in the faith, whose souls are now in heaven.

After taking a look a one-lesson excursion on what it means to praise God, we again approach the topic of prayer. Today, we examine the topic of praying for those who have died in the faith, whose souls are now in heaven.

Before we get to the “why,” we see if such praying is in line with the Christian faith.

The Lutheran Confessions and Prayer for the Dead

Our Confessions mention praying for the dead in one place, in passing.

“Regarding the adversaries’ quoting the Fathers about the offering for the dead, we know that the ancients speak of prayer for the dead, which we do not ban.” (Ap 24, para 94)

“Epiphanius declares that Aerius [Arius] maintained prayers for the dead are useless. He finds fault with this. We do not favor Aerius either.” (Ap 24, para 96).

- Although, a bit obtuse, agreeing that prayers for the dead are NOT useless is a way of saying what?

- If “prayers for the dead” are not useless but, instead, useful, what is the natural conclusion concerning praying for the dead?

- For Roman-Catholic theology, prayers for the sainted dead is a huge part of their theology. In our theological discussions with them during the 16th century, why do you think prayers for the dead barely got a mention (unlike purgatory)?

The Origin for Praying for the Dead in the Christian Church

On Mount Sinai, Moses pleaded to God to be merciful to His people. The Israelites had earlier decided to worship God through a golden calf, the symbol for one of the Egyptian pagan gods (Exodus 32:5). As part of his plea, Moses prayed:

Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, your servants, to whom you swore by yourself as you declared, “I will make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and will give your offspring all this land I promised them, and it will be their inheritance forever.” [Exodus 32:13]

When we read the account of the golden calf, we often miss the point that Moses prayed for Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Some later Old-Testament passages, show that praying for those who died in the faith was simply part of their understanding of the Old Covenant (see 2 Maccabees 12:38-42, 44).

After a battle, Israelite General, Judah Maccabee, found slain soldiers wearing amulets to pagan gods. Distraught, he gathered his men to pray for those who had died. The reason he prayed for them was “if he were not expecting the fallen to rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead” (2 Maccabees 12:44).

Note: The Lutheran Confessions operate from the worldview that the Apocrypha is Scripture, even calling 2 Maccabees “Scripture” (AP XXI, The Invocation of the Saints, para 9).

What is wrong and what is right with Judah’s actions:

- Right: He believed in the resurrection of the body, so that tied in to the reason for his prayer.

- Right: Praying for “the dead” is part of the faith.

- Wrong: He believed they died outside the faith but prayed to change their eternal status.

Irony: The Roman-Catholic Church uses this passage to support their doctrine of purgatory (Catechism of the Catholic Church, Section 1032). However, even Rome disagrees with praying for those who died outside the faith.

Sirach 7:33: “Give graciously to all the living; do not withhold kindness even from the dead.”

Prayers for the Dead in the New Testament

Jesus and Martha

Judah Maccabee prayed for the dead because of the resurrection of the body to come. We find the resurrection of the body even shaped the prayers for the dead within the New Testament.

Read John 11:17-27

- In vs. 22, what does Martha ask Jesus to do?

- Based on what had happened (Lazarus had died), what does the context provide for Martha’s expectation of what Jesus’ prayer will be?

- How does Jesus affirm her expectation based on when He next said to Martha? (vs. 23)

Jesus is now at the tomb of Lazarus with Martha.

Read John 11:38-39

- How does Martha react when Jesus asked for the stone covering Lazarus’ tomb to be removed?

- What does this tell us about what Martha did not expect from Jesus’ prayer?

- Based on the context and Jesus’ repeatedly bringing up of the resurrection, what does that reveal about the prayer practices of His day (which Jesus did not speak against)?

Paul and Onesiphorus

Read 2 Timothy 1:16

- What does Paul ask from God (a prayer) for the “household of Onesiphorus”? (vs. 16a)

- Whom does Paul not mention?

“he often refreshed me”: In 2 Timothy, Paul mentioned the family of Onesiphorus twice (here and in 2 Timothy 4:19), even though Onesiphorus had helped him in prison and served the congregation at Ephesus. Paul’s second mention of Onesiphorus is striking: He doesn’t ask Timothy to greet Onesiphorus but, instead, “Greet… the family of Onesiphorus” (2 Timothy 4:19).

Paul spoke of Onesiphorus’ earthly deeds in the past tense. Paul even praised “the service he rendered [past tense] at Ephesus,” without referring to any service that he is [present tense] rendering, there or elsewhere.

Why does Paul speak this way? Onesiphorus had died. That’s why Paul’s prayer in verse 16 makes all the more sense: “May the Lord grant mercy to the household of Onesiphorus” because Onesiphorus was no longer there.

Read 2 Timothy 1:18

- For whom does Paul pray in this verse?

- What is the “day?”

- This prayer is then for Onesiphorus in relation to what event?

We see throughout Scripture that the resurrection of the body shapes our prayers for the sainted dead. Their souls are in heaven, but they still have not come to the fullness of their salvation, which will take place on the Last Day.

Prayers for the Dead in the Lutheran Church

The historic practice within the Lutheran Church had prayers for the dead in their Prayer of the Church during the Divine Service. If we were to look at a typical Lutheran service during the 16th century, we would find in the prayers intercessions, special prayers, the Lord’s Prayer, and prayers for the sainted dead. (See Elmer Kiessling’s book, The Early Sermons of Luther and Their Relation to the Pre-Reformation Sermon by Zondervan, 1935, pg. 32, reprinted by AMS Press.)

Prayers for the Dead in the LC-MS

Refresh the soul that has now departed with heavenly consolation and joy, and fulfill for it all the gracious promises which in Your holy Word You have made to those who believe in You. Grant to the body a soft and quiet rest in the earth till the Last Day, when You will reunite body and soul and lead them into glory, so that the entire person who served You here may be filled with heavenly joy there. (Starck’s Prayer Book, Revised Concordia Edition, pg. 345 [Johann Friedrich Starck (1680-1756), published by CPH in English in 1921, reprinted in 2009])

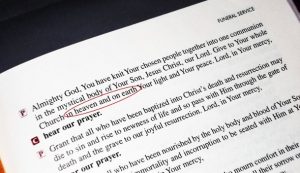

The funeral service in Lutheran Service Book has this prayer: “Give to Your whole Church in heaven and on earth Your light and Your peace…. Grant that all who have been nourished by the holy body and blood of Your Son may be raised to immortality and incorruption to be seated with Him at Your heavenly banquet.”

Appendix: What We Lost When We Stopped Praying for the Dead

Psychological Closure

Prayers for the dead—especially at a funeral—comfort those still living on earth. It does so because it affirms the communion of saints. It also helps provide psychological “closure” for those grieving. It allows those who are mourning to cry out to God in prayer for the loved one who has died. Such prayers have therapeutic value.

Our View of Salvation became Two-Dimensional

By not praying for the sainted dead, it’s easier for us to conclude that their salvation has already happened. After all, they are in heaven and have no chance of falling away from the faith, which is true. However, although saved, their salvation has not fully taken place. That will happen on the Last Day when body and soul will reunite and God will create a new heaven and a new earth. That is when the fullness of their salvation will happen.

What does that mean? It means that the saints in heaven are still living in faith and hope, awaiting the fullness of their salvation on the Last Day, just like we are. So, by praying for them, that practice helps us better understand our salvation.

Our View of the Church Became Flattened

When we stopped praying for the dead, our understanding of what it means to be Church changed. In Christ’s Church, an inseparable division does not exist between the Church Militant and Church Triumphant in all areas. For example: The saints in heaven pray to God as we do (Revelation 6:9-10). They are the great cloud of witnesses encouraging us to run the race of faith (Hebrews 12:1). They rejoice when a sinner repents on earth (Luke 15:9). As part of the Church, they are not fully disconnected from our lives, for they are part of the Communion of Saints, as are we.

When we don’t pray for those who are in God’s eternal presence, our poor practice of prayer begins to shape what we believe (lex orandi, lex credendi). We naturally begin to think that an insurmountable breech exists between the saints on earth and the saints in heaven. We can begin to think in terms of two churches: the one in heaven and the one on earth.

The Church includes those in the Church Militant and the Church Triumphant. We are in one Church. We are all one in the love of God the Father. Whether we are in time or in eternity, as members of the one, true Church, we still belong to the same family, and we still pray for one another. One does not stop being a member of the Church simply because he happens to die. Death does not sever the bond of mutual love that links together all the members of the Christ’s Church.