This is our pastor’s newsletter article for our March 2015 edition of our newsletter. In it, he leaves much out to keep the article a usable length. So, the article is not “bullet proof,” but it does, on the main, cover why the Old Testament contains the books that it does.

This is our pastor’s newsletter article for our March 2015 edition of our newsletter. In it, he leaves much out to keep the article a usable length. So, the article is not “bullet proof,” but it does, on the main, cover why the Old Testament contains the books that it does.

———-

In this article, we’ll explore how we got the Old Testament. Next month, I hope, to do the same for the New Testament.

To begin, we won’t look at how God the Holy Spirit inspired the writers of old. As Lutherans, we accept this as a given (at least for the canonical books of the Old Testament; we’ll get to that in a bit). Instead, we’ll look at historical events within the Church, showing how the Church eventually settled on a list of books that she affirmed as Old-Testament Scripture.

The Septuagint

We start with the Greek translation of the Old Testament, called the Septuagint. We start here because it happened to be the de-facto Old Testament for both Jesus and His Apostles. Knowing about the Septuagint may help you make sense of “disparities” between what you read in the Old Testament and the New Testament’s use of an Old-Testament passage. Before becoming a pastor, I looked up many passages in the Old Testament that New Testament writers used and thought “That doesn’t look like what my Old Testament reads.” Then, I didn’t know why; now I do.

So, why the difference? Our Old Testaments are based on the Masoretic Text that Jewish Scholars, known as the Masoretes, put together from the Hebrew texts they had between the 7th and 10th centuries. But the New Testament writers almost always referred to the Greek-language Old Testament, the Septuagint, which 70 Jewish scholars had translated in the 2nd century BC. And why wouldn’t they do that? The New Testament was written in Greek for Greek readers/hearers and the Septuagint was the Greek-Language Old Testament they all used!

If you were to examine how the New Testament uses the Old Testament, only looking at verses where a difference exists between the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint, you’d find 83 verses (at least, that’s what your pastor could find). Among those 83 verses, 77 verses use the Septuagint, six use what we find in the Masoretic text. In other words, the New Testament favors the Septuagint 93% of the time.

So, what books were in the de-facto Old Testament Septuagint, which Jesus and His Apostles used? The titles of the Old-Testament books in the Septuagint are different from the titles we use. But we can still figure it out:

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings], Paralipomena [1-2Chronicles], Job, the Psalter, the five books of Solomon [Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Wisdom, and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus)], the twelve Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, Tobias, Judith, Esther, Ezra [two books], Maccabees, two books.

What we find are books we recognize, some we don’t. We also find that some books in the Septuagint are longer than the Masoretic Text, such as Daniel, which has Bel and the Serpent and Song of the Three Young Men, and Esther. We also find books, which today, are part of the Apocrypha.

We also find the New-Testament writers—and Jesus—referring to those Apocrypha books in the New Testament. For instance, in one case, we find the Sadducees challenging Jesus. To do this, they brought up a story of a man who had married seven times (Matthew 22:23-28). They did this to contest what books made up the Old Testament AND, they hoped, to refute the resurrection of the body.

The Sadducees held that only Genesis through Deuteronomy was Scripture; they also didn’t believe in an afterlife or the resurrection of the body. So they adapted a story from the Apocrypha book of Tobit about a man who had married seven times. To refute them, Jesus said, “You are deceived, because you don’t know the Scriptures [Tobit is part of the Scriptures and, besides, you mangled the story] or the power of God [God has the power to raise the dead back to life]” (Matthew 22:29).

Early Church Listings of Old-Testament Books

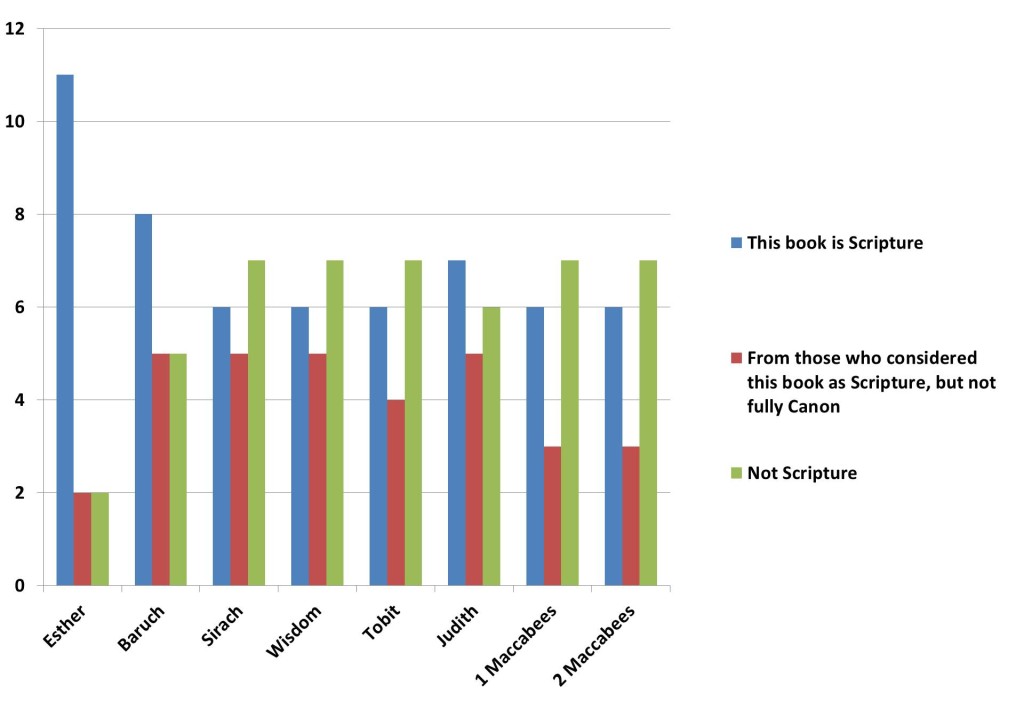

We now look at early Church councils and Church fathers who listed what books belonged in the Old Testament. What we find varies, but also a general consensus. We find some books that were universally accepted; others were contested. Among the eight books that were contested, looking at 13 lists between 160 and 397 AD,[1] we find:

What strikes us as odd is the idea that a book may be in Scripture but not be canon (books of Scripture from which we make doctrine). The Lutheran Church, from the beginning, understood this distinction, which is why to this day, for example, we don’t use the book of Revelation to make doctrine.

Three of the Church Fathers who had dealt with what books belong in the Old Testament are worth noting. Jerome (347 – 420 AD) contended that certain books did not belong in the Old Testament. His list of the Old Testament makes up, what is today, the Protestant Old-Testament Scriptures. Athanasius of Alexandria (297 – 373 AD) held that some Old-Testament books were not canon but still worthy of being read in Church and used as preaching texts. He called these books Anagignoskomena, books worthy of being read (basically the books of the Apocrypha). Cyril of Jerusalem (313 – 386 AD) classified some books as second-tier canon, Deuterocanon (again, basically the books of the Apocrypha). The Deuterocanon tradition eventually became the practice in the West, which the Lutheran Church inherited.

To settle this debate, the Church met in council in 397 AD at Carthage, which today is in Tunisia. In short, the Church rejected Jerome’s view and upheld that Athanasius’ and Cyril’s views were both acceptable. What the Council of Carthage did was simply recognize the books in the Septuagint as Old-Testament Scripture.

The Lutheran Church

When the Roman-Catholic Church excommunicated Martin Luther, starting the beginnings of the Lutheran Church, we simply accepted the Bible we had: The Roman Catholic Bible with the Deuterocanon.

Luther began translating the Bible into German. But he began to consider a number of books, for various reasons, as not Scripture. In the Old Testament, he considered Esther, Song of Songs, and the books of what today is the Apocrypha as not Scripture.

If Luther had his way, he would have removed those books from the Bible (he also would have removed James and Revelation from the New Testament, but that’s next month’s article). However, what we find Luther doing IS NOT removing those books. Despite his personal opinions, he knew that he didn’t have the authority to remove any books from the Bible!

What Luther did do was move the Deuterocanon (second-tier canon books) into a section called the Apocrypha. The Lutheran Church then moved from treating those books as Deuterocanon (second-tier canon) to Anagignoskomena, as worthy of being read and preached from in the Church, but not to make doctrine.[2] The Lutheran Church had adopted the other tradition, which the Council of Carthage had affirmed.

We find this to be the case in our Lutheran Confessions, which reference the Old Testament Apocrypha as part of Scripture.[3] We also find this to be the case as Lutheran pastors preached from the Apocrypha books and even had saint-day festivals remembering Tobias, Susanna, and Judith, all saints from the Apocrypha.

So, how did we end up with Bibles without the Apocrypha, which almost all of us now use? In short, what basically happened is that we adopted the shorter Old Testament that English-speaking Protestants around us starting using in the late 1700 and early 1800s, after they had removed the Apocrypha. But if you were to look in your Grandmother’s German Bible, even those printed by CPH, the Missouri Synod’s publishing house, you’d find all the books of the Apocrypha intact.

So, there you have it. The history ain’t pretty, but it’s always good to know how we ended up where we are, especially if where we are is now different from our Lutheran Confessions.

——-

[1] Melito, 160 AD; Origen, 225 AD; Cyril of Jerusalem, 348 AD; Hilary of Potiers, 360 AD; Cheltanham List, 360 AD; Council of Laodecia, 363 AD; Athanasius of Alexandria, 367 AD; Amphilocius of Iconium, 380 AD; Apostolic Canons, 380 AD; Gregory of Nanzianzus, 380 AD; Epiphanius of Salamis, 385 AD; Jerome, 390; Augustine, 397.

[2] Ironically, we find in Martin Chemnitz’ Enchiridion that the Lutheran Church adopted Athanasius’ view of the Old-Testament Anagignoskomena, but used Jerome’s language, Apocrypha.

[3] For example, Apology to the Augsburg Confession, section V, paragraph 158 and Apology to the Augsburg Confession, section XXI, paragraph 9.

For a related treatment on this topic, you can go here.